3.1 General history of lighthouses in Australia

The first lighthouse to be constructed along Australian soil was Macquarie Lighthouse, located at the entrance to Port Jackson, NSW. First lit in 1818, the cost of the lighthouse was recovered through the introduction of a levy on shipping. This was instigated by Governor Lachlan Macquarie, who had ordered and named the light.

The following century oversaw the construction of hundreds of lighthouses around the country. Constructing and maintaining a lighthouse were costly ventures that often required the financial support of multiple colonies. However, they were deemed necessary aids in assisting the safety of mariners at sea. Lighthouses were firstly managed by the colony they lay within, with each colony developing their own style of lighthouse and operational system. Following Federation in 1901, which saw the various colonies unite under one Commonwealth government, lighthouse management was transferred from State hands to the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service.

Lamps and optics – an overview

Lighthouse technology has altered drastically over the centuries. 18th century lighthouses were lit using parabolic mirrors and oil lamps. Documentation of early examples of parabolic mirrors in the United Kingdom, circa 1760, were documented as consisting of wood and lined with pieces of looking glass or plates of tin. As described by Searle, “When light hits a shiny surface, it is reflected at an angle equal to that at which it hit. With a light source is placed in the focal point of a parabolic reflector, the light rays are reflected parallel to one another, producing a concentrated beam”.8

In 1822, Augustin Fresnel invented the dioptric glass lens. By crafting concentric annular rings with a convex lens, Fresnel had discovered a method to reduce the amount of light absorbed by a lens. The Dioptric System was adopted quickly with Cordouran Lighthouse (France), fitted with the first dioptric lens in 1823. The majority of heritage-listed lighthouses in Australia house dioptric lenses made by others such as Chance Brothers (United Kingdom), Henry-LePaute (France), Barbier, Bernard & Turenne (BBT, France) and Svenska Aktiebolaget Gasaccumulator (AGA of Sweden). These lenses were made in a range of standard sizes, called orders—see Appendix 2. Glossary of lighthouse Terms relevant to Gabo Island Lighthouse.

Early Australian lighthouses were originally fuelled by whale oil and burned in Argand lamps, and multiple wicks were required in order to create a large flame that could be observed from sea. By the 1850s, whale oil had been replaced by colza oil, which was in turn replaced by kerosene, a mineral oil.

Figure 9. Incandescent oil vapour lamp by Chance Brothers (Source: AMSA)

Figure 9. Incandescent oil vapour lamp by Chance Brothers (Source: AMSA)

Figure 10. Dioptric lens on display at Narooma (Source: AMSA, 2011)

Figure 10. Dioptric lens on display at Narooma (Source: AMSA, 2011)

In 1900, incandescent burners were introduced. This saw the burning of fuel inside an incandescent mantle which produced a brighter light with less fuel within a smaller volume. Light keepers were required to maintain pressure to the burner by manually pumping a handle as can be seen in Figure 9.

In 1912, Gustaf Dalén, a Swedish engineer, was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for a series of inventions relating to acetylene-powered navigation lights. Dalén’s system included the sun valve, the mixer, the flasher, and the cylinder containing compressed acetylene. Due to their efficiency and reliability, Dalén’s inventions led to the gradual de-staffing of lighthouses. Acetylene was quickly adopted by the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service from 1915 onwards.

Figure 11. Dalén's system – sun valve, mixer and flasher (Source: AMSA)

Figure 11. Dalén's system – sun valve, mixer and flasher (Source: AMSA)

Large dioptric lenses, such as that shown in Figure 10, gradually decreased in popularity due to cost and the move towards unmanned automatic lighthouses. By the early 1900s, Australia had stopped ordering these lenses with the last installed at Eclipse Island in Western Australia in 1927. Smaller Fresnel lenses continued to be produced and installed until the 1970s when plastic lanterns, still utilising Fresnel’s technology, were favoured instead. Acetylene remained in use until it was finally phased out in the 1990s.

In current day, Australian lighthouses are lit and extinguished automatically using mains power, diesel generators, and solar-voltaic systems.

3.2 The Commonwealth Lighthouse Service

When the Australian colonies federated in 1901, they decided that the new Commonwealth government would be responsible for coastal lighthouses—that is, major lights used by vessels travelling from port to port—but not the minor lights used for navigation within harbours and rivers. There was a delay before this new arrangement came into effect. Existing lights continued to be operated by the states.

Since 1915, various Commonwealth departments have managed lighthouses. AMSA, established under the Australian Maritime Safety Authority Act 1990 (Cth), is now responsible for operating Commonwealth lighthouses and other aids to navigation, along with its other functions.

3.3 Gabo Island: a history

Aboriginal history

Further consultation is required with traditional stakeholders.

Early European history

The 1770 expedition to Australia, led by naval explorer Captain James Cook, first made landfall on 19 April 1770 near modern-day Point Hicks, Victoria. That same day, Cook recorded in his journal:

Friday 20th9. – In the P.M. and most part of the night had a fresh Gale Westerly, with Squalls, attended with Showers of rain. In the A.M. had the Wind at S.W., with Severe weather, At 1 P.M. saw 3 Water Spouts at once; 2 were between us and the Shore, and one at some distance on our Larboard Quarter. At 6, shortened sail, and brought too for the Night, having 56 fathoms fine sandy bottom. The Northernmost land in sight bore N. by E. (half) E., and a small island lying close to a point on the Main bore W., distant 2 Leagues. This point I have named Cape Howe; it may be known by the Trending of the Coast which is N. on one Side and S.W. on the other. Lat 37°28’ S.; Long 210°3’W. It may be known by some round hills upon the main just within it.10

The ‘small island lying close’ identified by Cook would later be known as Gabo Island.

Later expeditions recorded the prevalence of seals in Bass Strait which led to an explosion of sealing in the region. Although no conclusive evidence has been found to suggest Gabo Island and its harbour were used as a sealing base, it was used as a base for whaling in the early 19th century. Dr Imlay’s whaling establishment operated on Gabo Island for a period of time, however by 1846 all that remained of the station was three deserted huts.11

3.4 The first Gabo Island Lighthouse (1853-1862)

By the 1840s, it was determined by the various Australian colonies that Bass Strait required lighting. The Strait was traversed frequently by shipping, and its treacherous waters had claimed many vessels and lives over the course of the early 19th century. No coastal lighthouse had been constructed in Australia since Macquarie Light in 1818, the country’s first lighthouse, meaning “there was no systematic approach to the lighting of the long and dangerous coast of Australia”.12 The Cape Howe region was presented to the colonies in 1841 as a possible site for a lighthouse. Sir John Franklin, Governor of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), addressed the matter with Sir George Gipps, Governor for New South Wales, who in turn agreed that “a Light on Cape Howe would also be most desirable”.13

No further action was taken until 1845 when the Select Committee of the Legislative Council of New South Wales reiterated these statements, and in 1846 Gabo Island was surveyed and officially recommended by Charles J Tyers, Commissioner of Crown Lands in District Gipps Land. Tyers detailed that the firm sandy soil found at the island’s highest point at the centre of the landmass was ideal for the construction of a lighthouse.14

Tenders were called in June 1846 and a Mr John Morris was accepted as contractor. Excavations commenced on the island where it was assumed a foundation would be located approximately 2.5 metres below the surface. However, 12 months later, workers had excavated to a depth of 20 meters and no solid foundation had been found. With costs now expected to exceed the funds available, debates ensued on whether it was better to choose a different site. Work on the Island eventually came to a standstill as additional arguments sprouted over government finances and which colony Gabo Island would belong to following the separation of New South Wales and Victoria in 1850.15

While these arguments ensued, tragedy struck. Monument City, the first steamer to cross the Pacific, was returning from Melbourne on 15 May 1853 when it ran aground on Tullaberga Island a mere five kilometres west of Gabo Island. 33 lives were lost and it was agreed across the board that such an incident would not have occurred had a light been established. In the days following the tragedy, it was declared Gabo Island lay within the colony of Victoria and that a temporary lighthouse was to be built ‘as soon as possible’ with costs split between both colonies.16

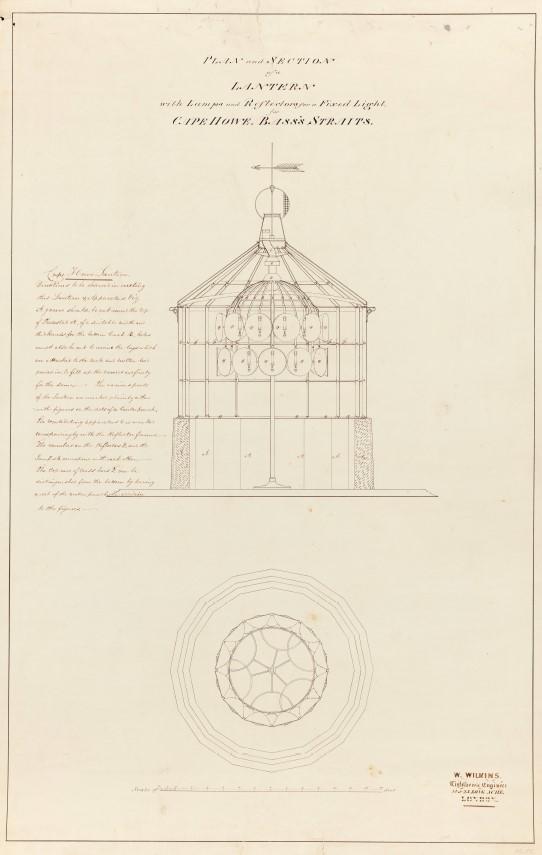

Figure 12. Plan and section of a lantern with lamps and reflectors for a fixed light for Cape Howe, Bass Straits (Gabo Island Lighthouse: Working Plan), 1846. NAA: A9568, 6/4/2 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Figure 12. Plan and section of a lantern with lamps and reflectors for a fixed light for Cape Howe, Bass Straits (Gabo Island Lighthouse: Working Plan), 1846. NAA: A9568, 6/4/2 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

By September 1853, a prefabricated wooden tower and a Wilkins lantern ordered some time ago and left in storage, were shipped to Gabo Island and erected at the original site excavated. On 28 November 1853, the tower was lit for the first time. The Cornwall Chronicle described the tower as:

a skeleton timber erection, painted White; the roof and framing of the Lantern painted Red: and the Ventilating Ball painted Yellow. It stands nearly at the centre of the Island, about three-quarters of a mile from its southern point, upon a sand-hill 157ft 6in. above the sea. The centre of the Light is 21 ft 6in. above the sand…

The Light is a fixed White Light of the First Class, consisting of 24 Catoptric Lamps in 2 ranges, illuminating the whole horizon. The Light is eclipsed by a small range of sand-hills from S. 15° E. to S. 4° W. (in all 19 degrees), to a distance averaging about 2 miles out to sea.

It is estimated that the Light can be seen 20 miles distance in clear weather.17

The lighthouse was christened ‘Flinders Light’, after navigator and cartographer Matthew Flinders, and remained lit for nine years before a permanent light was eventually built.

3.5 The second Gabo Island Lighthouse (1862-present)

By 1859, Flinders Light had fallen into disrepair and calls for the construction of a permanent tower to replace the 1853 timber frame were brought to the forefront. Like the existing light, the cost of the new tower was to be split between the New South Wales and Victorian colonies.

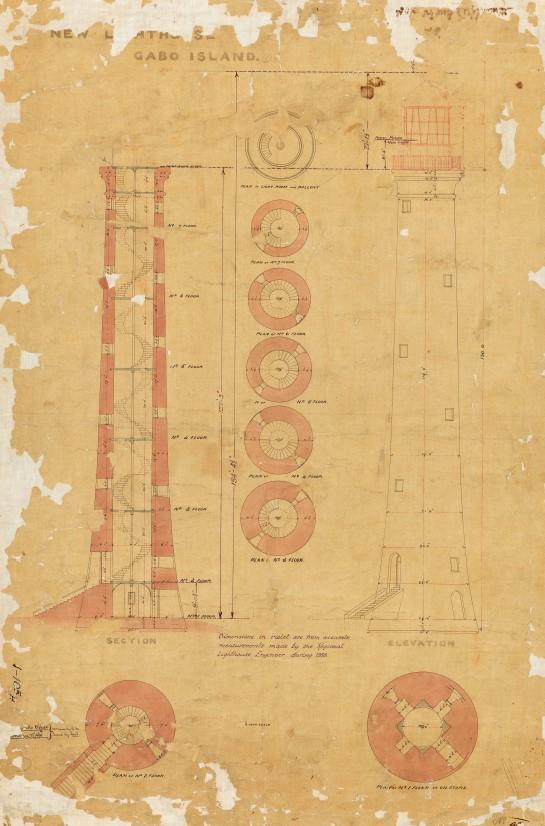

Design

The new lighthouse was designed as a “tapering column of smooth red granite topped with a new pattern Chance Brothers lantern containing a fixed light”.18 This design was chosen due to the high amount of durable, red granite quarried from the island. By October 1859, the Chance Bros. lantern had been ordered. It was decided the lighthouse should be built on the south-eastern shore of the Island instead of replacing the timber structure in the centre.

Records differ in crediting the design of the new Gabo Island Lighthouse. Some attribute the design to William Wilkinson Wardell who was charged with public works in Victoria at the time, while others determine the design was created by Charles Maplestone who was Clerk of Works in Melbourne.19 A majority agree that while Wardell did visit Gabo Island in 1860, Charles Maplestone was responsible for the design, with Maplestone writing in a letter:

Charles Maplestone Born in England in 1809, Charles Maplestone journeyed to Australia at age 44 after a career working under eminent civil engineer, William Cubitt. In 1853, Maplestone joined the Public Works Department in Melbourne, and by 1857 he had commenced work on coastal and harbour lights. His was responsible for the design of a number of lighthouses including Cape Schanck (Vic), Gabo Island (Vic) and Wilsons Promontory (Vic). Maplestone retired in 1869 spending his remaining years as a celebrated wine maker until his death in 1878. |

Figure 13. New lighthouse: Gabo Island, 1860. NAA: A9568, 6/4/12 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Figure 13. New lighthouse: Gabo Island, 1860. NAA: A9568, 6/4/12 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

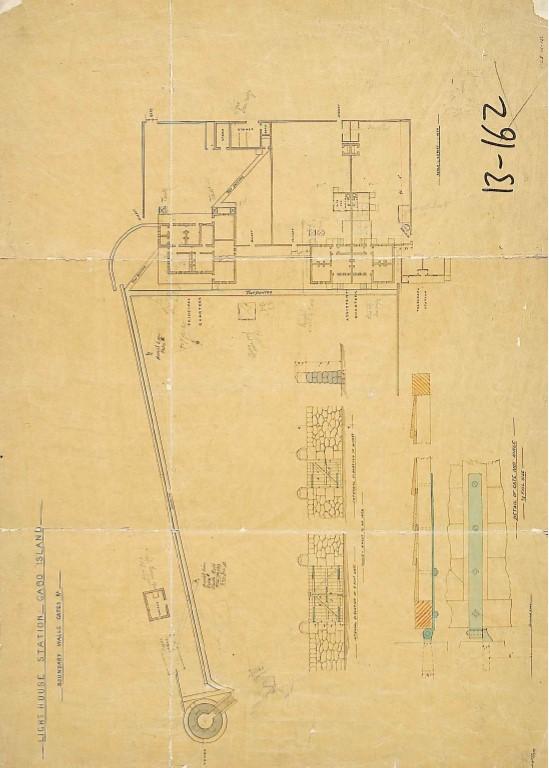

Figure 14.Lighthouse station – Gabo Island – Boundary Walls, Gates etc, 1884. NAA: A9568, 6/4/14 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Figure 14.Lighthouse station – Gabo Island – Boundary Walls, Gates etc, 1884. NAA: A9568, 6/4/14 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Construction

Tenders were called in July 1860 and awarded to Melbourne contractor Robert Huckson for £14,950. Construction started shortly after, however issues arose within months of commencement with masons complaining of poor provisions and threatening to leave the island. It was found that Huckson had established a ‘Truck System’ on the island where he “had compelled them [the workers] to enter into a new contract by which the wages were higher, but by which they were to purchase all their provisions from him at an exorbitant price”.21 By 1862, Huckson was declared bankrupt by reason of ‘heavy losses in a contract for erecting lighthouse at Gabo Island, and pressure of creditors’ liabilities’.22

The contract was handed over to Alexander Cairns and Henry Mills on 20 February 1862, and by May of that same year it was reported that the lighthouse was complete.23 On 20 August, Flinders Light was officially extinguished and the new Gabo Island Lighthouse was lit for the first time.

Equipment when built

Upon completion, Gabo Island Lighthouse stood as a 47 metre, circular dressed granite structure. The tower supported a Chance Bros. 12’ diameter lantern and 920 millimetre 6 panel 315° 1st Order fixed lens with 45° catoptric reflector. The light was recorded as having an intensity of 7000 c.d. and a range of 20 miles in good, clear weather.24

The tower was accompanied by a new head keeper’s cottage and two assistant keeper cottages. Although the Flinders Light lantern was removed, the wooden structure remained on the island for a number of years as well as the former keepers’ cottages.

3.6 Lighthouse keeping

The lighthouse was originally operated by a head keeper, two assistant keepers and their respective families. Although inhabitants were secluded from the mainland, at various times throughout the years Gabo Island would be filled with a number of workmen quarrying the island’s granite, effectively breaking the isolation.25

Telegraphic communications were established on the Island in 1870 with a line reaching across the channel on posts and eventually run along the seabed. A telegraph office, erected beside the assistant keeper cottages, was originally of timber design until 1887 when a mass concrete residence and office was designed and constructed in its place.26

Figure 15. Photograph of Gabo Island Lighthouse and keepers, 1978. NAA: A6180, 25/7/78/9 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Figure 15. Photograph of Gabo Island Lighthouse and keepers, 1978. NAA: A6180, 25/7/78/9 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Throughout the duration of World War II, naval personnel were stationed on Gabo Island in corrugated iron huts, and air force personnel manned a radar station erected on the site of Flinders Light.27

There is no concise date on when the keepers were removed from the Island and the site de-staffed.

3.7 Chronology of major events

The following table details the major events to have occurred on Gabo Island from 1853 to present.

| Date | Event |

| 28 November 1853 | Flinders Light on Gabo Island lit for first time. |

| 1860 | Construction begins on permanent Gabo Island Lighthouse. |

| 20 August 1962 | Flinders Light extinguished and Gabo Island Lighthouse lit for first time. |

| 1870 | Telegraphic communications established on Gabo Island.28 |

| 1887 | Timber telegraph office upgraded to mass concrete residence and office.29 |

| 1895 | Extreme weather washes away 228 feet of the stone wall on Gabo Island.30 |

| 18 July 1928 | Assistant lighthouse keeper, Percival Field dies aboard rescue ship after falling 80 feet from flag mast at lightstation31 |

| May 1930 | A ‘serious operation’ is performed on Mrs Broderick, a keepers’ wife, on-site at the station. The destroyer HMAS Anzac takes Mrs Broderick to the mainland to recover.32 |

| 1938-1945 | Naval units stationed on Gabo Island throughout World War II, and air force personnel man radar station on site.33 |

| 1962 | Original balcony balustrade replaced. |

| 1993 | Light automated. |

3.8 Changes and conservation over time

The following section details the changes and conservation efforts to have been carried out at Gabo Island Lighthouse since its construction in 1862.

The Brewis Report

Commander CRW Brewis, retired naval surveyor, was commissioned in 1911 by the Commonwealth Government to report on the condition of existing lights and to recommend any additional ones. Brewis visited every lighthouse in Australia between June and December 1912, and produced a series of reports published in their final form in March 1913. These reports were the basis for future decisions made in relation to each individual lighthouses and provide a snapshot of the Gabo Island Lightstation in the early 20th century.

Recommendations made by Brewis for Gabo Island Lighthouse included: the installation of an occulting screen, clockwork mechanism, and 85 mm incandescent mantle, the discontinuation of the red auxiliary light, alteration of the fog signal, the provision of an efficient Morse lamp, and the removal of the danger light platform and lightning conductor.34

Gabo Island Light.(20 miles from Green Cape.) Lat. 37° 34’ S., Long. 149° 55’ E., Chart No. 3169.- Established 1862. Last altered, 1909. Lloyd’s Signal Station. Character.- Main Light.- One white, with red sectors. Catadioptric. Fixed. Candle-power – white, 15,000 c.p.; red, 3,750 c.p. Illuminant, vaporized kerosene; 55 mm. incandescent mantle. Circular granite tower, 156 feet. Height of focal plane, 179 feet. Auxiliary Danger Light.- Red; fixed; exhibited from base of same tower as main light. Visibility.- Main Light.- Red, through an arc of 20 degrees, from 204° (S. 14° W. Mag.) to 224° (S. 34° W. Mag.); white, through an arc of 136 degrees, from 224° (S. 34° W. Mag.) to 55° (N. 45° E. Mag.); red through an arc of 39 degrees, from 55° (N. 45° E. Mag.) to 94° (N. 84° E. Mag.), and obscured elsewhere. Visible, in clear weather – white, for a distance of about 20 nautical miles; red, 10 nautical miles. Auxiliary Danger Light.- Visible, in clear weather, 3 miles seaward. Fog Signal.- Two explosive rockets fired in quick succession every ten minutes. Optical Apparatus.- Chance Bros., 1860. Catadioptric. Fixed lens. Focal radius, 36 inches. Six panels with one catoptric mirror. Condition and State of Efficacy.- The tower , lantern, and optical apparatus are in good condition and serviceable. The dwellings were repaired in 1911. The light requires to be given a distinctive character. The period of the fog signal is too long for the requirements of modern navigation. The auxiliary red danger light is shown to warn a vessel of her close approach to the shore. In thick weather it may not be visible. (Caution in Light List.) Three light-keepers are stationed here. Communication.- Telephone to Eden, 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. Visited quarterly by Government steamer. Coastal steamers fortnightly, weather permitting; contract under notice to expire. Morse lamp at station, but of low power. Fogs.- Not frequent; experienced chiefly in December and January. Soundings.- The soundings on the chart in this locality are of a complete and suitable nature, and the only legitimate and unerring guide to the safety of a vessel in this vicinity is the use of the lead, giving the navigator a sure indication of his distance from the shore. A mariner who relies on sighting the auxiliary red light (already rendered worthless by the Caution in the Light List) as a means of keeping his vessel out of danger and neglects to use the lead, undoubtedly trusts to a false security, and hazards the safety of his vessel and the lives of those on board. Recommended.-

|

Alterations to the light

The following table details the changes made to the Gabo Island light since its exhibition in 1862.

| Date | Alteration |

| 1862 | Chance Bros 12’ dia. lantern and 920 mm 6 panel 315° first order fixed lens with 45° catoptric reflector. Intensity: 7,000 c.d. |

| 10 July 1894 | 5th Order red auxiliary light installed at base of tower. |

| 1 Jan 1913 | Auxiliary light discontinued. |

| 2 July 1913 | Occulting shutter and clockwork installed 85 mm IOV burner Intensity: White 15,000 c.d. Red 3,750 c.d. |

| 1917 | Automatic acetylene with red and white sectors Intensity: White 13,000 c.d. Red 5,000 c.d. |

| 1934-35 | Conversion to electric with triple diesel generators. First Order lens replaced with Chance Bros 4th Order 3 panel lens. Fixed red light installed above main light. Intensity: White 750,000-927,000 c.d. 35 Red 12,000 c.d. |

| 25 Feb 1992 | Light converted to solar. 4th Order lens replaced with FA251 beacon. Intensity: 30,000 c.d. |

| May 2006 | FA251 beacon replaced with Vega VRB-25 beacon. Intensity: 24,816 c.d. |

| 2020 | Vega VRB-25 beacon replaced with Tideland Nova-250 beacon. |

Recent conservation works

The following table details recent conservation works carried out on the lighthouse by AMSA and its contractors.

| Date | Works completed |

|---|---|

| 2012 |

|

| 2019 |

|

3.9 Summary of current and former uses

From its construction in 1862, Gabo Island Lighthouse has been used as a marine AtoN for mariners at sea. Its AtoN capability remains its primary use.

The former lightkeeper’s quarters are now used to house Parks Victoria rangers carrying out caretaking duties on the island.

3.10 Summary of past and present community associations

Aboriginal associations

Further consultation is required with traditional stakeholders.

Local, national and international associations

Gabo Island is considered a significant site of Victorian and Australian history. The island and lightstation maintain strong familial associations due to the lighthouse’s extensive history as a manned site.

As a recognised habitat for various faunal colonies, Gabo Island is associated locally, nationally and internationally with wildlife conservation.

3.11 Unresolved questions or historical conflicts

There exists a lack of information in some areas of the lighthouse’s history, such as the exact date the site was de-staffed. Research of this topic did not provide a specific year keepers were removed from the island. Widespread automation and and de-staffing in Australian lighthouses occurred from 1975 onwards, and in an 1983 report ‘Lighthouses: do we keep the keepers?’ it was recommended Gabo Island Lighthouse be reduced to two staff.36 It can only be presumed that the lighthouse was de-staffed sometime around 1993 when the site was automated.

It is also unclear what the intensity of the light became when the 1st order lens was replaced in 1934-1935. Searle determines that the new light had an intensity of 927,000 c.d. while newspaper reports of the time determined it to have 750,000 c.d.37

3.12 Recommendations for further research

Recommendations for further research will be listed here in future versions of the plan.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Footnotes

![]() 8 Searle. G, First Order: Australia’s Highway of Lighthouses, Seaside Lights: SA, (2013), page 34

8 Searle. G, First Order: Australia’s Highway of Lighthouses, Seaside Lights: SA, (2013), page 34

![]() 9 Nautical days start at noon.

9 Nautical days start at noon.

![]() 10Captain W.J.L. Wharton (ed)., Captian Cook’s Journal 1768-71, Elliot Stock: London (1893); Ivar Nelsen, Patrick Miller & Terry Sawyer, Conservation Plan: Gabo Island Lightstation, Victoria, (1992), pg. 10.

10Captain W.J.L. Wharton (ed)., Captian Cook’s Journal 1768-71, Elliot Stock: London (1893); Ivar Nelsen, Patrick Miller & Terry Sawyer, Conservation Plan: Gabo Island Lightstation, Victoria, (1992), pg. 10.

11 ‘Lighthouse at Cape Howe,’ Sydney Morning Herald, June 3, 1846, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/28650004

![]() 12 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992) pg. 11.

12 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992) pg. 11.

13 ‘Votes and Proceedings of the NSW Legislative Council’, 1841, in Ivar Nelsen, et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 12.

![]() 14 Garry Searle, First Order, (2013) pg. 87; ‘Light houses, Bass’s Straits No. 1,’ The Melbourne Argus, Oct 16, 1846, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/4760264

14 Garry Searle, First Order, (2013) pg. 87; ‘Light houses, Bass’s Straits No. 1,’ The Melbourne Argus, Oct 16, 1846, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/4760264

![]() 15 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 13-14; Garry Searle, First Order, (2013), pg. 88.

15 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 13-14; Garry Searle, First Order, (2013), pg. 88.

![]() 16 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan (1992), pg. 15; Garry Searle, First Order, (2013), pg. 90-89.

16 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan (1992), pg. 15; Garry Searle, First Order, (2013), pg. 90-89.

![]() 17 ‘Flinders Light, Gabo Island,’ The Cornwall Chronicle, March 8, 1854, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/65714387

17 ‘Flinders Light, Gabo Island,’ The Cornwall Chronicle, March 8, 1854, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/65714387

18 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 16

19 Garry Searle, First Order (2013), pg. 127; Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 16-17.

![]() 20 Charles Maplestone, Letter to S.W. Rix Beccles 12 April 1859, Charles Maplestone Diary. City of Melbourne Collection, pg. 168.

20 Charles Maplestone, Letter to S.W. Rix Beccles 12 April 1859, Charles Maplestone Diary. City of Melbourne Collection, pg. 168.

![]() 21 Garry Searle, First Order, (2013) pg. 127

21 Garry Searle, First Order, (2013) pg. 127

22 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 18-19.

23 Garry Searle, First Order, (2013), pg. 127; Ivar Nelsen et al, Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 19.

![]() 24 ‘Notice to Mariners,’ Portland Guardian and Normanby General Advertiser, Sept 9, 1862 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/64626922

24 ‘Notice to Mariners,’ Portland Guardian and Normanby General Advertiser, Sept 9, 1862 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/64626922

![]() 25 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 19.

25 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 19.

![]() 26 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 20.

26 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 20.

![]() 27 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 22.

27 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 22.

![]() 28 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 19.

28 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 19.

![]() 29 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 20.

29 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 20.

30 Garry Searle, First Order (2013), pg. 128; ‘Damage to the Gabo Island Lighthouse,’ The Daily Telegraph, Oct 3, 1895 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/238550319

![]() 31 Garry Searle, First Order (2013), pg. 130; ‘Gabo Island tragedy: Lighthouse-keeper’s death,’ The Argus, Jul 19, 1928 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3944650

31 Garry Searle, First Order (2013), pg. 130; ‘Gabo Island tragedy: Lighthouse-keeper’s death,’ The Argus, Jul 19, 1928 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3944650

32 Garry Searle, First Order (2013), pg. 133.

![]() 33 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 22.

33 Ivar Nelsen et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 22.

34 C.R.W. Brewis, Lighting of the east coast of Australia: Cape Moreton to Gabo Island (Including coast of New South Wales, Department of Trade and Customs (1913), pg. 12.

![]() 35 ‘Higher power for Gabo Island Lighthouse,’ The Argus, Feb 22, 1934, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/1174181

35 ‘Higher power for Gabo Island Lighthouse,’ The Argus, Feb 22, 1934, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/1174181

![]() 36 Ivar Nelsen, et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 23; Lighthouses: Do we keep the keepers?, Report from the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Expenditure, Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, 1983.

36 Ivar Nelsen, et al., Conservation Plan, (1992), pg. 23; Lighthouses: Do we keep the keepers?, Report from the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Expenditure, Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, 1983.

![]() 37 Garry Searle, First Order, pg. 133; ‘Higher power for Gabo Island Lighthouse,’ The Argus, Feb 22, 1934 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/11741812

37 Garry Searle, First Order, pg. 133; ‘Higher power for Gabo Island Lighthouse,’ The Argus, Feb 22, 1934 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/11741812