3.1 General history of lighthouses in Australia

The first lighthouse to be constructed along Australian soil was Macquarie Lighthouse, located at the entrance to Port Jackson, NSW. First lit in 1818, the cost of the lighthouse was recovered through the introduction of a levy on shipping. This was instigated by Governor Lachlan Macquarie, who ordered and named the light.

The following century oversaw the construction of hundreds of lighthouses around the country. Constructing and maintaining a lighthouse were costly ventures that often required the financial support of multiple colonies. However, they were deemed necessary aids in assisting the safety of mariners at sea. Lighthouses were firstly managed by the colony they lay within, with each colony developing their own style of lighthouse and operational system. Following Federation in 1901, which saw the various colonies unite under one Commonwealth government, lighthouse management was transferred from state hands to the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service.

Lamps and optics: an overview

Lighthouse technology has altered drastically over the centuries. Eighteenth century lighthouses were lit using parabolic mirrors and oil lamps. Documentation of early examples of parabolic mirrors in the United Kingdom, circa 1760, were documented as consisting of wood and lined with pieces of looking glass or plates of tin. As described by Searle, “When light hits a shiny surface, it is reflected at an angle equal to that at which it hit. When a light source is placed in the focal point of a parabolic reflector, the light rays are reflected parallel to one another, producing a concentrated beam”.8

In 1822, Augustin Fresnel invented the dioptric glass lens. By crafting concentric annular rings with a convex lens, Fresnel had discovered a method of reducing the amount of light absorbed by a lens. The Dioptric System was adopted quickly with Cordouran Lighthouse (France), which was fitted with the first dioptric lens in 1823. The majority of heritage-listed lighthouses in Australia house dioptric lenses made by others such as Chance Brothers (United Kingdom), Henry-LePaute (France), Barbier, Bernard & Turenne (BBT, France) and Svenska Aktiebolaget Gasaccumulator (AGA of Sweden). These lenses were made in a range of standard sizes, called orders—see ‘Appendix 2. Glossary of lighthouse Terms relevant to Goods Island Lighthouse’.

Early Australian lighthouses were originally fuelled by whale oil and burned in Argand lamps, and multiple wicks were required in order to create a large flame that could be observed from sea. By the 1850s, whale oil had been replaced by colza oil, which was in turn replaced by kerosene, a mineral oil.

Figure 8. Incandescent oil vapour lamp by Chance Brothers (Source: AMSA)

Figure 8. Incandescent oil vapour lamp by Chance Brothers (Source: AMSA)

Figure 9. Dioptric lens on display at Narooma (Source: AMSA)

Figure 9. Dioptric lens on display at Narooma (Source: AMSA)

In 1900, incandescent burners were introduced. This saw the burning of fuel inside an incandescent mantle which produced a brighter light with less fuel within a smaller volume. Light keepers were required to maintain pressure to the burner by manually pumping a handle as can be seen in Figure 8.

In 1912, Swedish engineer Gustaf Dalén, was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for a series of inventions relating to acetylene-powered navigation lights. Dalén’s system included the sun valve, the mixer, the flasher, and the cylinder containing compressed acetylene. Due to their efficiency and reliability, Dalén’s inventions led to the gradual de-staffing of lighthouses. Acetylene was quickly adopted by the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service from 1915 onwards.

Figure 10. Dalén's system - sunvalve, mixer and flasher (Source: AMSA

Figure 10. Dalén's system - sunvalve, mixer and flasher (Source: AMSA

Large dioptric lenses, such as that shown in Figure 9, gradually decreased in popularity due to cost and the move towards unmanned automatic lighthouses. By the early 1900s, Australia had stopped ordering these lenses with the last installed at Eclipse Island in Western Australia in 1927. Smaller Fresnel lenses continued to be produced and installed until the 1970s when plastic lanterns, still utilising Fresnel’s technology, were favoured instead. Acetylene remained in use until it was finally phased out in the 1990s.

In the current day, Australian lighthouses are lit and extinguished automatically using mains power, diesel generators, and solar-voltaic systems.

3.2 The Commonwealth Lighthouse Service

When the Australian colonies federated in 1901, they decided that the new Commonwealth government would be responsible for coastal lighthouses—that is, major lights used by vessels travelling from port to port—but not the minor lights used for navigation within harbours and rivers. There was a delay before this new arrangement came into effect. Existing lights continued to be operated by the states.

Since 1915, various Commonwealth departments have managed lighthouses. AMSA, established under the Australian Maritime Safety Authority Act 1990 (Cth), is now responsible for operating Commonwealth lighthouses and other aids to navigation, along with its other functions.

3.3 Goods Island: a history

Aboriginal history

Goods Island is in the Kaiwalagal region (Endeavour Strait) and is known by Kaurareg people traditionally as Palilag, and the island is referred to in the Waubin Dreaming Story. Waubin of Muralag (Prince of Wales Island), was feared by men and known to wield kubai (a throwing stick known as a woomera), a kalak (a spear) and baidamal baba. Waubin would collect wives for every man he killed, and he lived with them at his home, Rabau Nguki. Eventually Waubin had to leave Rabau Nguki with his wives, and he led them to Badhaukuth on the western side of Muralag, then to Gialag (Friday Island), before reaching Palilag. Although Waubin continued on to Nomi (Round Island), Koimilai (a point on Kiriri), he left some of his wives at Palilag and they all turned to stone. As for Waubin, he stepped into the sea near Gobau Ngur, a rocky headland of Kiriri, and turned to stone.9

Although there was no long-term inhabitation of the Palilag, it is understood the island was regularly visited and used as fishing grounds both before, during and after European settlement. At least two fish traps have been recorded on Palilag, one being the Bertie Bay fish trap.10 Pearling began in the Torres Strait in 1868, and by 1877, 16 pearling firms were operating on Thursday Island. Palilag was one of the key bases for the Torres Strait pearling industry, and the activity became cemented in the culture of the region. Following the establishment of the lightstation, visits to the island continued.

Early European history

The Torres Strait was named after the Spanish captain, Luis Vaz de Torres, who sailed through the Straits in 1606 on his way to the Philippines. Individual islands retained their traditional names, but also acquired European names in the years following de Torres’s exploration. Prominent European explorers such as the navigator Captain James Cook, Vice-Admiral William Bligh and the navigator Captain Matthew Flinders sailed through the Straits in the late eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries.

Goods Island was given its European name by Flinders after Peter Good, the botanical gardener on board his vessel the Investigator during the 1802 voyage. Over time, the name ‘Goods’ was misspelt as ‘Goode’ and the island is referred to as such in literature throughout the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.

In Flinders’ account of Goods Island, he wrote:

“In the morning of Nov. 2, the wind being more moderate and at E. S. E., we steered between Hammond's Island and the north-western reef, with soundings from 6 to 9 fathoms. Another island appeared beyond Hammond's, to the south- west, which, as it had no name, I called Good's Island, after Mr. Good, the botanical gardener; and we hauled up for it, passing a rock and a small reef between the two. On seeing an extensive shoal ahead, which would have carried us off the land to go round it, we anchored in 7 fathoms, dead coral and shells, with the north end of Hammond's Island bearing N. 64° E., four or five miles. The botanical gentlemen landed on Good's Island; and in the afternoon I took these bearings amongst others, from a hill near its south-west end.

The ship, distant 1¼ miles N. 58° 0' W. Wallis' Isles, over the Shoal Cape of Bligh, S. 23 5 W. Booby Isle, centre, S. 80 0 W.

Northern isles, the westernmost visible, N. 28° 10' to 24 5 W.

Hawkesbury Island, N. 9 15 to 4 0 W. North-west reef, its apparent termination, N. 38 50 W.”11

Vessels regularly passed through the Torres Strait in the first half of the nineteenth century, increasingly so after Philip Parker King recommended traversing the inner route in 1833.12 In 1834, the British East India Company’s trading monopoly was broken and Sydney-based traders took more interest in the western Pacific as they were able to supply the Chinese market with goods such as beche-de-mer and sandalwood. The strategic importance of shipping routes to Queensland’s north stimulated the establishment of the Somerset settlement on the eastern coast of Cape York, just south of the tip, looking over Albany Passage to Albany Island. Queensland had hopes that Somerset would become a ‘second Singapore’.13

In 1872, Queensland annexed the islands up to 60 miles from Cape York. The Somerset settlement was moved to Thursday Island in 1875-77 and in 1879, the remaining islands were annexed and the Torres Strait islands became part of Queensland.14

3.4 Building a lighthouse

Why Goods Island?

The reefs and shoals of the Great Barrier Reef, at the southern end of the inner route, and in the Torres Strait, were notoriously dangerous for shipping. Ipili Reef, close to Goods Island, claimed several ships, including the paddle steamer Phoenix (1855).15 There were 64 wrecks on the inner route between 1840 and 1850.16 The importance of trade with India and China, as well as the developing pearling industry, put pressure on the Queensland government to install navigational aids in the Torres Strait.

On 14 July 1882, the Torres Strait pearling industry wrote to the Colonial Secretary requesting a light at the western end of the Torres Strait. Pearling began in the Torres Strait in 1868 with 16 pearling firms operating on Thursday Island in 1877 and Goods Island was one of the key bases for the Torres Strait pearling industry. The request was referred to the Colonial Treasurer as minister responsible for ports and harbours and then to the port master, G.P. Heath for a report. Heath agreed that a light was essential.17

Booby Island to the west of Goods Island had previously been suggested as a potential lighthouse site at the 1873 Inter-colonial Conference, however no action had been taken. Heath had already established a number of navigational aids on the Queensland coast, initially harbour lights and beacons, and added lighthouses when new ports opened in the more treacherous waters on the North Queensland coast.

A signal station had previously been established on Goods Island c. 1877, and it was determined by Heath that the signalman already stationed on the island could also operate a lighthouse. Heath wrote in his annual report: “In Torres Straits a good position light is required at Goode Island to point out the position of the entrance to Normanby Sound and the Prince of Wales Channel. This light could be attended to by the signalman stationed on the island”.18 However, fiscal restraint exercised by the 1879 McIlwraith Government delayed the initial construction of the lighthouse.

Heath’s Notice to Mariners (No. 27 of 1882) dated 13th October 1882 stated:

‘On and after this date, a Temporary Light will be exhibited from the Signalman’s Cottage on Goode Island at an elevation of 250 feet above the sea level. The Light will be visible from a distance of 7 or 8 miles when clear of the North end of Hammond Island and North about, until it bears E.N.E and also in Normanby Sound between N by E and N.W by N.19

When exhibited, the light was described in Pugh’s Almanac:

‘A bright light is shown from sunset to sunrise from the veranda of the signalman’s cottage on Goode Island. It is about 250 feet above sea level and is visible over an area from N.E by E round by North to W.S.W, to a distance of 8 or 9 miles in fine weather.’20

Heath visited the Torres Strait, including Goods Island, in 1886 and selected the site for the lighthouse on the highest point, Western Hill, near Tucker Point, at 327 feet (99.7 metres) above sea level.21 Heath noted in his report of this trip to the Torres Strait that the increase in ship traffic through the straits, particularly from Cooktown, was most likely due to the discovery of gold on the Palmer River in 1873 and migration to the goldfields.22

Design and construction

No requests for tenders were issued for the construction of the lighthouse, indicating that the lighthouse was likely constructed by the Queensland Government as opposed to hiring private contractors. It is believed that Goods Island Lighthouse was the only lighthouse of this type to be built entirely by the Queensland Government during the late-nineteenth century.23

An order was made for a light destined for Goods Island, and this was captured in correspondence to the Queensland treasurer in 1886:

‘For Goode Island, one fixed 4th order apparatus, to illuminate an arc of 180°, & to be fitted with totally reflecting glass mirrors. The lamp to be fitted with three burners & spare reservoir & tubing. The burners to be fitted with 2 wicks, & without the central dispersers, to be fitted with Farquhars chimneys, & the level of the oil to stand at a distance of two inches below the top of the burner. The apparatus to be adjusted to an elevation of 250 feet .’24

It is difficult to fix an exact construction date of the Goods Island lighthouse. G P Heath’s Torres Strait sailing directions, published in the 1885 Pugh’s Almanac, stated that the “temporary light would be replaced in the ensuing year”.25

In December 1886, a notice appeared in the Queensland Telegraph newspaper stating: “Goode Island Lighthouse- This lighthouse which has been constructed in sections in Brisbane, will be forwarded to its destination by the next steamer leaving for Thursday Island. It will, when erected on Goode Island be a vast improvement on the present light which marks the entrance into the harbour at Thursday Island.”26

This was followed in 1887 by the publication of a ‘Notice to Mariners’ stating:

“Goode Island- Exhibition of Permanent Light; Discontinuation of Temporary Light….The Queensland Government has given further notice, that on 22nd March, 1887, the permanent light will be exhibited from a lighthouse erected on the western hill (327 feet) of Goode Island, near Tucker Point, and that the temporary light would then be discontinued…..The signal station, heretofore situated on a hill near the centre of Goode Island, has been transferred to the western hill.”27

It is, therefore, probable that the lighthouse was erected between about December 1886 and March 1887.

Equipment when built

Upon completion, Goods Island Lighthouse stood as a timber framed, corrugated iron-clad structure. Apart from its heavy cross-bracing, the tower was otherwise similar to the previous iron-plated design for lighthouses in Australia built at that time. The sheeting was specially formed with tapering corrugations to suit the conical shape of the tower.28 As Goods Island was elevated in parts, there was no need for the lighthouse to be particularly tall. The tower was just below 5 metres high and located 105 metres above sea level.

The tower was fitted with the specified 4th Order Chance Brothers dioptric with a fixed light, a flasher, and a ‘totally reflecting’ glass mirror.29 The light covered more than 180 degrees. The light was described as being visible between the bearings of north east by east through south and south west and would be visible in fine weather for 24 miles.30 Goods Island was the fourth lighthouse of a total of only nine of this type to be constructed in Queensland.31

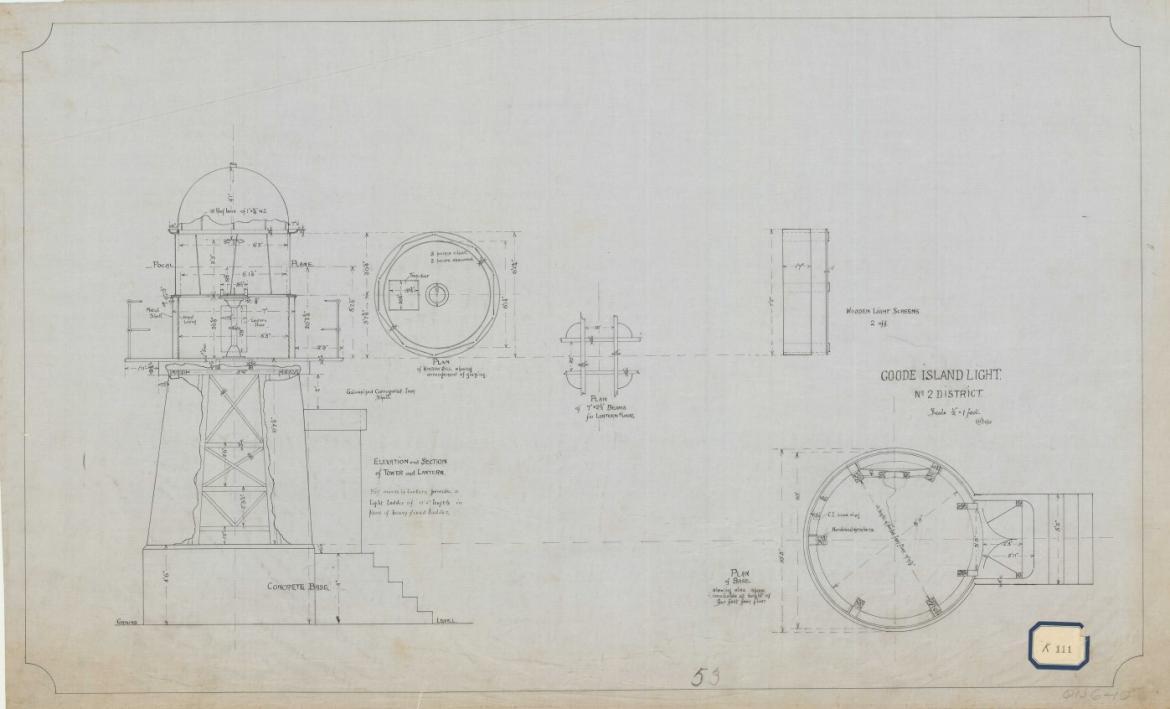

Figure 11. Goode Island Tower - details, 1922. Courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: J2776, QN 06 010 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)32

Figure 11. Goode Island Tower - details, 1922. Courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: J2776, QN 06 010 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)32

Light keeping

Goods Island Lighthouse was overseen by a number of keepers when it was first lit in 1887. By the turn of the twentieth century, Goods Island, which by now included a lightstation, signal station, pilot station and pear-shelling base, had become home to various families. In 1902, a school was established on the southern shore of the island and by 1904, fourteen children were enrolled.33 Gradually however, inhabitants on Goods Island dwindled, and by 1912 it was reported that only two families remained on the island.34

The lighthouse launch Roonganah travelled twice a month from Thursday Island bringing mail and stores for the keepers stationed at the island. Landing points were either at the pilot station jetty on the southeast shore or at the foot of the tramway at half tide or above.

Throughout the duration of the Second World War, the keepers were removed from the lightstation, and operation of the light was overseen by the military as naval surveillance was carried out in the waters of the Torres Strait. This arrangement only lasted for the duration of the war and keepers were reinstated in the early 1950s.

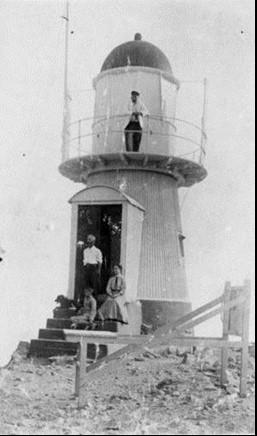

Figure 12. A family group at the Goods Island Lighthouse ca. 1909 (Courtesy of the State Library of Queensland)35

Figure 12. A family group at the Goods Island Lighthouse ca. 1909 (Courtesy of the State Library of Queensland)35

Alongside tending to the light, keepers were required to report maintenance on the lighthouse and accompanying residence – reports that shed light on the condition of the lightstation over time. In 1957, the keepers reported on ‘repairing washaway on trolley line’, ‘painting cream inside engine shed’, ‘painting radio mast and outside engine shed’, ‘painting outside of outhouses’, ‘painting water tanks’. In 1958 it was revealed that a new water tank was constructed at the station, and in 1959, loose paint was scraped from inside the lantern room.36

The rainfall station closed on 20 November 1973 when the last lighthouse keeper, Townsend, departed.

Second World War

Goods Island and its lightstation were changed dramatically following the onset of World War II (1939-1945). The need to fortify Goods Island had been previously analysed as early as 1907, and a 1913 contour survey of the island clearly demonstrated that Tucker Point, Quoin Point and Tessy Head at the western and eastern extremes of the island were slated for defence purposes.37 However, it was not until World War II that Goods Island was fully utilised for defence strategies along the northern coastline of Australia.

The Department of the Interior constructed emplacements and other defence works on Goods Island, commencing in October 1940. By July 1941, guns had been assembled and proof-fired, and by December a three storied command post and searchlight engine rooms were comstructed with equipment and stores positioned. Five foot fortress searchlights installed at both Milman Hill (on Thursday Island) and Goods Island batteries were utilised to illuminate areas of water, through which attacking vessels had to pass in order to reach the main land of Australia.

In 1942 Navy personnel requested permission to manage the lights on Goods Island under the supervision of Senior Mechanic Kerlin. Lighthouse keeper Everett was withdrawn on 12 November 1942, allowing personnel exclusive use of the keeper’s cottage and station. It was agreed the arrangement was only to be for the duration of the war.38

During this period, the Australian defence forces erected numerous buildings and structures along the western side of Goods Island, remnants of which remain within close proximity to the lighthouse today. Evidence of this period of the island’s history can be seen in the observation building and radar screen, the generator shed as well as inscriptions made in concrete near the flagstaff. It is assumed that concrete retaining walls were also constructed around the lighthouse around the same time of the observation building’s construction.

The Navy remained at Goods Island until the early 1950s when the last vestiges of military installations were abandoned. Some of these constructions were removed in 1953 and the radar screen was declared obsolete.

3.5 Chronology of major events

The following table details the major events to have occurred at Goods Island Lighthouse.

| Date | Event |

| 1902 | School established on Goods Island for the keepers’ children. |

| 1907 | Earthquake strikes Goods Island, lighthouse reported as damaged.39 |

| 3 June 1927 | Lighthouse Keeper Valentine Cecil Cloherty passes away due to heart strain believed to be from carrying stores to Goods Island Lighthouse during a period where the tramway was broken down. Commonwealth Government later instructed to pay compensation to Cloherty’s widow.40 |

| 11 January 1936 | Lighthouse and signal station struck by lightning. Telephone, flagstaff and walls of engine shed damaged.41 |

| 1939 | The Hydrographic Admiralty corrected the name ‘Goode Island’ to Goods Island.42 |

| 1940 | Department of the Interior construct emplacements on Goods Island in response to the outbreak of World War II. |

| July 1941 | Guns assembled on Goods Island. |

| December 1941 | A command post and searchlight engine room established on Goods Island. |

| 1942 | The Australian Navy take over full operation of the lighthouse, Lighthouse Keeper Everett withdrawn 12 November. |

| c. 1950s | Navy relinquish control of lighthouse and withdraw from the island. |

| 1953 | Some of the structures built for the war removed. |

| 1957 | Submarine cable laid at Goods Island allowing telephonic connection from the lighthouse to Thursday Island.43 |

| 1973 | Lighthouse destaffed. |

3.6 Changes and conservation over time

The following section details the changes and conservation efforts to have been carried out at Goods Island Lighthouse since its construction.

The Brewis Report

Commander CRW Brewis, retired naval surveyor, was commissioned in 1911 by the Commonwealth Government to report on the condition of existing lights and to recommend any additional ones. Brewis visited every lighthouse in Australia between June and December 1912, and produced a series of reports published in their final form in March 1913. These reports were the basis for future decisions made in relation to the individual lighthouses and provide a snapshot of the lightstation in the early 20th century.

Brewis recommended that Goods Island be given a distinctive character, have the light’s intensity increased, and that an assistant keeper be employed.44

Goode Island Light. (15 miles from Booby Island.) Lat. 10° 34’ S., Long. 142° 09’ E., Chart No. 691. RECOMMENDED. – |

Alteration to the light

The following table details the changes to the Goods Island light since its exhibition in 1887.

| Date | Alteration |

| 7 February 1937 | Light converted to automatic operation, acetylene light source installed. |

| 1957 | 5 horsepower Kelly and Lewis engine replaced with 5 horsepower diesel engine. |

| c. 1970s | Flagstaff removed |

| 1988 | Light converted to solar powered operation, halogen light source fitted within lantern. |

For information on current light details, see ‘Appendix 4 Goods Island Lighthouse current light details’.

Recent conservation works

The following table details the recent conservation works to have occurred at Goods Island Lighthouse.

| Date | Work |

| 1955 | Balcony balustrades repaired and reinstalled. |

| November 2013 | Lantern dome patch holes repaired. |

| 2021 | Major refurbishment works including:

|

3.7 Summary of current and former uses

From its construction in 1886, Goods Island Lighthouse has been used as a marine AtoN for mariners at sea. Its AtoN capability remains its primary use. The quarters, once used to house keepers stationed at the tower, are no longer on site.

The lighthouse, and the island as a whole, were also utilised for naval efforts throughout the duration of World War II. By the early 1940s, various structures built for the purpose of surveilling surrounding waters had altered the original layout of the lightstation. Keepers were removed from the island, and the cottages were for the full use of military personnel. The lighthouse retained its original purpose as an AtoN and was operated by those stationed on Goods Island.

3.8 Summary of past and present community associations

Kaurareg past and present associations

Kaurareg are the traditional custodians and knowledge-holders for the region. Kaurareg and the wider Torres Strait community maintain strong connections to Palilag. Today, the island is often visited by traditional custodians for fishing, hunting, camping and other reasons.

Local, national and international associations

The lighthouse maintains strong familial links due to its extensive history as a staffed site. Numerous families were stationed at Goods Island, and their experiences were captured by contemporary sources.

The lighthouse and larger landscape of the island also maintain strong association with the Australian war effort following the outbreak of the Second World War. The military personnel stationed on the island were responsible for tending to the light, and remnants found at site shed light on naval surveillance during this period. \

3.9 Unresolved questions or historical conflicts

It is uncertain when designs of Goods Island Lighthouse were originally drawn, and when construction of the tower commenced. It is understood that work was underway by 1886, however there is no clear idea of when workers were first mobilised to site.

3.10 Recommendations for further research

Further investigation on the design and construction process would be beneficial in understanding the significance of Goods Island as the only lighthouse of its type to have been constructed by the Queensland Government. Clarification on why a Government-constructed process was chosen, as opposed to hiring a private contractor, would assist these understandings.

Further research on the keepers and military personnel stationed at Goods Island would be beneficial in understanding the social history of the lightstation and island as a whole throughout the late-19th to mid-20th centuries.

Footnotes

8 Garry Searle, First Order: Australia’s Highway of Lighthouses, (SA: Seaside Lights, 2013), 34.

9 Torres Strait Regional Authority, hammond: Sustainable Land Use Plan (2010), adapted from “Myths & Legends of the Torres Strait”, Lawrie, 1970.

10 Rowland, J and Ulm, S., Indigenous Fish Traps and Weirs of Queensland cited in QAR, No. 8, Vol. 14 (2011)

11 Matthew Flinders, A voyage to Terra Australis (London: W. Bulmer and Co., 1814), 119-120.

12 The Great Barrier Reef Inner Route (or ‘inner route’) is the principal shipping lane that extends from Booby Island to Cape Grafton, passing along the northern and eastern seaboard of Australia between the mainland and the Great Barrier Reef. The northern portion of the ‘inner route’ from Booby Island to Cairns is actually part of the Great North East Channel and includes the Prince of Wales Channel through the Torres Strait, to the north of Goods Island; while the Normanby Sound, to the south of Goods Island is used as the western approach to Thursday Island.

Ian Hawkins Nicholson, Via Torres Strait: A maritime history of the Torres Strait Route and the Ship’s Post Office at Booby Island (Queensland: Roebuck Series, 1996), 116.

13 Jean Farnfield, “The moving frontier: Queensland and the Torres Strait,” in Lectures on North Queensland History, ed. B. J. Dalton (Townsville: James Cook University, 1974), 65.

14 Queensland Coast Islands Act 1879 (Qld)

15 “Loss of the steamer Phoenix,” Sydney Morning Herald, October 1, 1855

16 R. G. Ledley, “Early Torres Strait and Coast Pilots’ Service,” Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland 5, no. 5, (1957): 1274

17 Winifred Davenport, Harbours and Marine: Port and harbour development in Queensland from 1824 to 1985 (Brisbane: Department of Harbours and Marine, 1986), 177

18 Department of Ports and Harbours, Votes and Proceedings (Queensland Legislative Assembly, 1882), 1072

19 “Notice to mariners,” Northern Territory Times and Gazette, March 24, 188

20 Pugh’s Almanac (1894), cited in Davenport, Harbours and Marine, 177.

21 Gordon Reid, From dusk till dawn: A history of Australian Lighthouses (A&C Black, 1988), 105.

22 Department of Ports and Harbours, Votes and Proceedings (Queensland Legislative Assembly, 1886), 607; Nicholson, Via Torres Strait, 260.

23 Davenport, Harbours and Marine, 177.

24 Letter 140 of 1886 (Q.SD.A TRE/A32) cited in J. H. Thorburn, “Major Lighthouses of Queensland,” Queensland Heritage 1, no. 7 (1967): 21.

25 Thorburn, “Major lighthouses of Queensland,” 19.

26 “Goode Island Lighthouse,” Telegraph (Brisbane), December 21, 1886,

27 “Notice to Mariners,” Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, June 25, 1887,

28 Peter Marquis-Kyle, “Queensland’s timber and tin lighthouses: 19th century colonial innovation,” (Paper presented at 3rd Australasian Engineering Heritage Conference, 2009), 4. accessed October 2020

29 “Notice to Mariners,” London Gazette, May 24, 1887

30 “Notice to Mariners.”

31 John Ibbotson, Lighthouses of Australia: A visitor’s guide (Surry Hills: Australian Lighthouse Traders, 2003), 46.

32 NAA: J2776, QN 06 010.

33 District Inspector to Under Secretary, 8 December 1902, Department of Public Instruction, Goode Island School No 456, Administration file, Series 12607, Item 14715, Queensland State Archives; Annual returns of schools, 1903-1911, Department of Public Instruction, Series 12596, Item 10552, Queensland State Archives.

34 E. W. Jones to Under Secretary, 11 June 1912, Department of Public Instruction, Goode Island school No 456, Administration file, Series 12607, Item 14715, Queensland State Archives.

35 John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland Neg No: 55583.

36 Lightstation logs, Goods Island 1957-8, Series BP206/11, Item 1702516, National Archives of Australia; Lightstation logs, Goods Island 1959-60, Series BP206/11, Item 1702518, National Archives of Australia.

37 “Goode Island fortifications,” Morning Post (Cairns), July 31, 1907

38 B. Hooper, “Good’s Island,” Torres Strait Historical Society Bulletin 1 (n.d.): 7

39 “Earthquake at Thursday Island,” Daily Telegraph, October 29, 1907

40 “Compensation apportioned,” Brisbane Courier, July 9, 1928

41 “Struck by lightning,” Daily Advertiser (Wagga Wagga), January 13, 1936; “Keeper and wife shaken but unhurt,” Telegraph (Brisbane), January 11, 1936

42 “Goode Island,” Daily Commercial News and Shipping List (Sydney), January 27, 1939

43 “New submarine cable to Goode Island,” Torres News (Thursday Island), October 29, 1957

44 C.R.W. Brewis, Report on the lighting of the north-east coast of Australia Torres Strait to Cape Moreton: Recommendations as to existing lights and additional lights (Department of Trade and Customs: Acting Government Printer, 1912), 10.