3.1 General history of lighthouses in Australia

The first lighthouse to be constructed along Australian soil was Macquarie Lighthouse, located at the entrance to Port Jackson, NSW. First lit in 1818, the cost of the lighthouse was recovered through the introduction of a levy on shipping. This was instigated by Governor Lachlan Macquarie, who ordered and named the light.

The following century oversaw the construction of hundreds of lighthouses around the country. Constructing and maintaining a lighthouse were costly ventures that often required the financial support of multiple colonies. However, they were deemed necessary aids in assisting the safety of mariners at sea. Lighthouses were firstly managed by the colony they lay within, with each colony developing their own style of lighthouse and operational system. Following Federation in 1901, which saw the various colonies unite under one Commonwealth government, lighthouse management was transferred from state hands to the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service.

Lamps and optics: an overview

Lighthouse technology has altered drastically over the centuries. Eighteenth century lighthouses were lit using parabolic mirrors and oil lamps. Documentation of early examples of parabolic mirrors in the United Kingdom, circa 1760, were documented as consisting of wood and lined with pieces of looking glass or plates of tin. As described by Searle, “When light hits a shiny surface, it is reflected at an angle equal to that at which it hit. With a light source is placed in the focal point of a parabolic reflector, the light rays are reflected parallel to one another, producing a concentrated beam”.12

In 1822, Augustin Fresnel invented the dioptric glass lens. By crafting concentric annular rings with a convex lens, Fresnel had discovered a method of reducing the amount of light absorbed by a lens. The Dioptric System was adopted quickly with Cordouran Lighthouse (France), which was fitted with the first dioptric lens in 1823. The majority of heritage-listed lighthouses in Australia house dioptric lenses made by others such as Chance Brothers (United Kingdom), Henry-LePaute (France), Barbier, Bernard & Turenne (BBT, France) and Svenska Aktiebolaget Gasaccumulator (AGA of Sweden). These lenses were made in a range of standard sizes, called orders—see ‘Appendix 2. Glossary of lighthouse Terms relevant to Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse’.

Early Australian lighthouses were originally fuelled by whale oil and burned in Argand lamps, and multiple wicks were required in order to create a large flame that could be observed from sea. By the 1850s, whale oil had been replaced by colza oil, which was in turn replaced by kerosene, a mineral oil.

In 1900, incandescent burners were introduced. This saw the burning of fuel inside an incandescent mantle which produced a brighter light with less fuel within a smaller volume. Light keepers were required to maintain pressure to the burner by manually pumping a handle as can be seen in Figure 8.

Figure 9. Incandescent oil vapour lamp by Chance Brothers (Source: AMSA

Figure 9. Incandescent oil vapour lamp by Chance Brothers (Source: AMSA

Figure 10. Dioptric lens on display at Narooma (Source: AMSA)

Figure 10. Dioptric lens on display at Narooma (Source: AMSA)

In 1912, Swedish engineer Gustaf Dalén, was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for a series of inventions relating to acetylene-powered navigation lights. Dalén’s system included the sun valve, the mixer, the flasher, and the cylinder containing compressed acetylene. Due to their efficiency and reliability, Dalén’s inventions led to the gradual demanning of lighthouses. Acetylene was quickly adopted by the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service from 1915 onwards.

Figure 11. Dalén's system - sunvalve, mixer, flasher and cylinder (Source: AMSA)

Figure 11. Dalén's system - sunvalve, mixer, flasher and cylinder (Source: AMSA)

Large dioptric lenses, such as that shown in Figure 9, gradually decreased in popularity due to cost and the move towards unmanned automatic lighthouses. By the early 1900s, Australia had stopped ordering these lenses with the last installed at Eclipse Island in Western Australia in 1927. Smaller Fresnel lenses continued to be produced and installed until the 1970s when plastic lanterns, still utilising Fresnel’s technology, were favoured instead. Acetylene remained in use until it was finally phased out in the 1990s.

In the current day, Australian lighthouses are lit and extinguished automatically using mains power, diesel generators, and solar-voltaic systems.

3.2 The Commonwealth Lighthouse Service

When the Australian colonies federated in 1901, they decided that the new Commonwealth government would be responsible for coastal lighthouses—that is, major lights used by vessels travelling from port to port—but not the minor lights used for navigation within harbours and rivers. There was a delay before this new arrangement came into effect. Existing lights continued to be operated by the states.

Since 1915, various Commonwealth departments have managed lighthouses. AMSA, established under the Australian Maritime Safety Authority Act 1990, is now responsible for operating Commonwealth lighthouses and other aids to navigation, along with its other functions.

3.3 Sugarloaf Point: a history

Aboriginal history

The history of the Myall Lakes National Park stretches back many thousands of years. The landscape and its natural resources provided for the Worimi Aboriginal People. Family clans upheld hunter-gatherer lifestyles and thrived off the native fauna and flora, the coastal waterways and freshwater lakes. The park contains a number of significant sites showcases this extensive history, including middens, scar trees, petroglyphs and campsites.

Further consultation with Traditional Stakeholders is required.

Early European history

In May of 1770, Captain Cook sailed along the NSW coastline in the Endeavour and made the first European record of the coastal area adjacent to the Myall Lakes, including Sugarloaf Point and the rocky outcrops known as Seal Rocks.13 It is believed that the first Europeans to set foot in the area were survivors of the Jane, the Edwin, and the Governor shipwrecks in 1816 which occurred within the vicinity of the rocks. Allegedly five survivors made it ashore, including the captain of the Edwin, and travelled by foot to the settlement of Newcastle.14

In 1825, the area formed part of a land grant to the newly established Australian Agricultural Company. However, much of the coastal area was reverted back to the Crown.15

3.4 Why a lighthouse on Sugarloaf Point?

By the early to mid-19th century, shipping along the coast had increased exponentially. Port Macquarie and Moreton Bay to the north had developed into penal settlements, and cedar trade along the coast meant that Port Stephens, to the south of Sugarloaf, was regularly used as a haven for shipping. It became obvious that the rocky outcrops of Sugarloaf Point and Seal Rocks were shipping hazards. A number of ships were wrecked around this time including the Sally in 1843 and the schooner the Mary Ann only one month after.16

A Select Committee of the NSW Legislative Council was appointed in 1863 to consider the construction of additional lighthouses on the coast. The Committee identified that there was 600 kilometres of unlit coast between Cape Moreton and Port Stephens.17 Marine Board President Captain Hixson, who held a grand plan to light the coast of NSW “like a highway”, recommended that a lighthouse be erected on Seal Rocks, rather than on the mainland on Sugarloaf Point.18 As explained by Garry Searle in First Order: Australia’s Highway of Lighthouses, ‘These rocks were a navigational turning point and steamers leaving Sydney at night arrived there before daylight’.19 However it was a further ten years before funds were allocated towards the construction of the Lighthouse.

In April 1873, the Marine Board attempted to visit Seal Rocks with Colonial Architect James Barnet, however they found it impossible to land on any of the offshore locations.20 It was decided that a new site on Sugarloaf Point be selected instead, and the area for a lighthouse was marked out on the mainland.21 The first sum of £10,000 was placed on the estimates and in October 1873 was voted in for a Lighthouse on Seal Rocks.22

3.5 Building a lighthouse

Design and construction

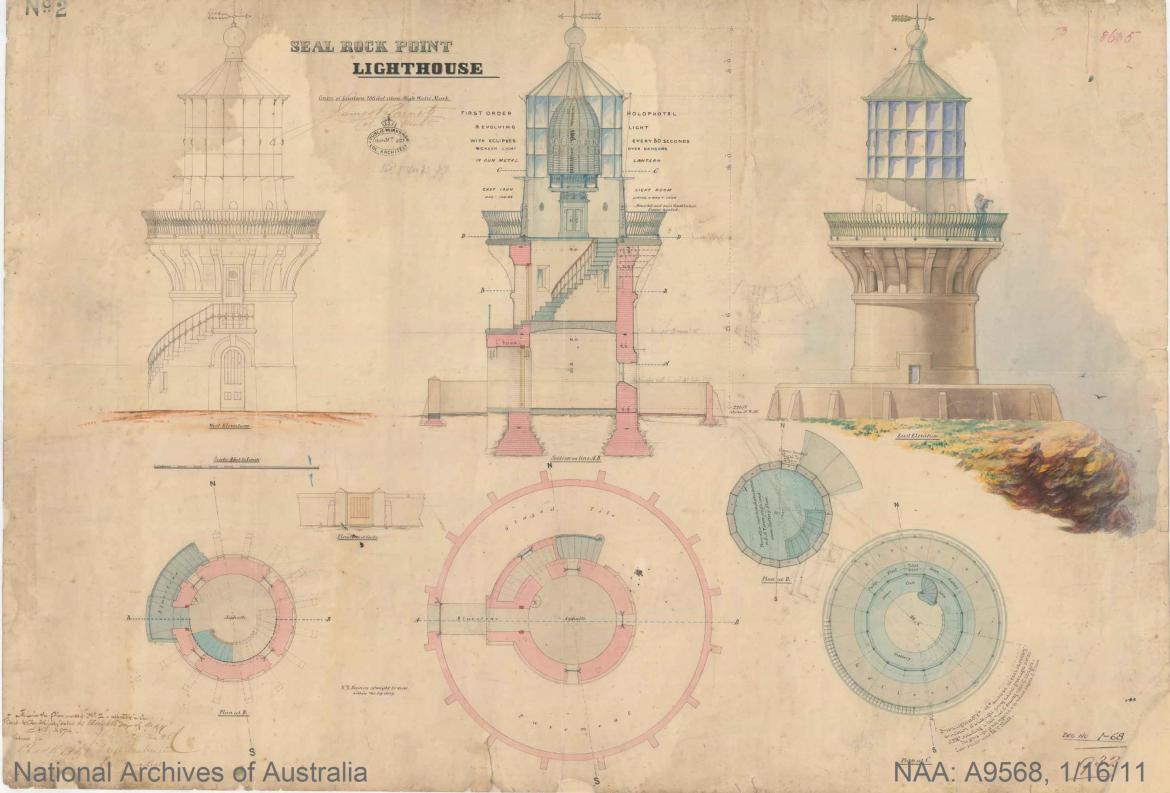

Once the funds were made available, Barnet prepared plans for the proposed lightstation. The designs featured a rendered brick tower with curved balustrades and an external stairway, and the larger lightstation included three Regency-style keepers’ cottages.

Tenders were invited in February 1874, and a site visit was arranged for Barnet, the tenderers and some of the Marine Board, landing in Seal Rocks Bay. In April 1874, the calls for tender were readvertised as no tenders had been accepted.23

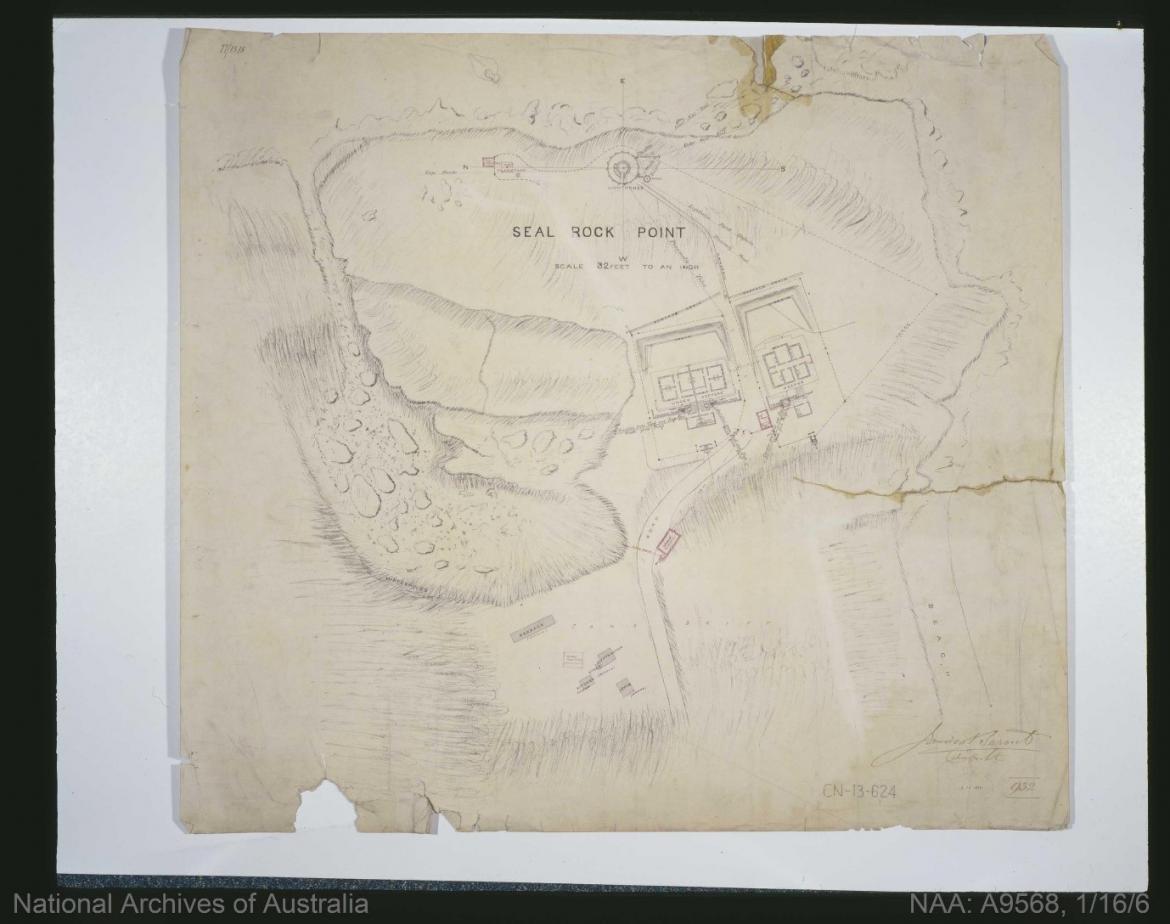

The tender of Mr John McLeod, £13,383, was accepted shortly afterwards which included the erection of the lighthouse and quarters, the fixing of the lantern and carriage, as well as the road to Myall Lake.24 The contractors also constructed a 1500 feet long jetty at Sugarloaf Bay and Boat Beach primarily for the offloading of construction materials for the lightstation.25

In November 1873, a 16-panel 1st order lens was ordered from Messrs. Chance Bros. & Co., a prominent company located near Birmingham, England. In May 1874, Chance Bros. recommended that a 4th order subsidiary dioptric apparatus be added to the order to assist lighting the rocks below the mainland. The lantern and subsidiary light were delivered to Sydney and landed safely at Seal Rocks bay by July 1875.26

Construction of the keepers’ cottages and various outbuildings required the headland to be cut into and the construction of stone retaining walls in order to provide the cottages with shelter. The fill removed from these works was allegedly used to level the site of the tower.27

For the duration of the works, a construction camp consisting of a barracks, contractor’s office, kitchen office store and school was built along the road to Myall Lake.28

The construction of the lighthouse was officially complete by 29 October 1875.

Figure 12. Design plan of Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse, 1874. Courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A9568, 1/16/11 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Figure 12. Design plan of Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse, 1874. Courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A9568, 1/16/11 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Equipment when built

Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse was officially lit on 1st December 1875, the first Barnet-designed lighthouse to be completed.29 The lighthouse consisted of two stories approximately 21 feet 6 inches above the ground floor and 11 feet in diameter on the inside. With asphalted ground and intermediate floors, and an iron lantern floor, the tower was built of brick and cemented inside and out.

Barnet’s plans had been followed meticulously, including the installation of the unique external stairs. The balcony, consisting of sixteen bluestones, also incorporated what would become a classic feature of Barnet’s lighthouses: the outward curved gunmetal balustrades.30

The 1st order lens with a white flashing light had a recorded intensity of 50,000 candelas. The green subsidiary light located below the lantern room lit the rocky outcrops below, covering approximately three miles with an arc of sixty degrees and intensity of 150 candelas.31

The keepers’ cottages stood on the headland’s southern side, the Head Keeper’s cottage consisting of five rooms including a pantry, detached kitchen and water closet. The Assistant Keeper‘s cottages were semi-detached, three-roomed residences with a store, a detached kitchen and water closet.

3.6 Lighthouse keeping

The first head keeper to be stationed at Sugarloaf Point was Henry Hoadley, and his assistants Daniel Watson and George Morris. Lightkeepers were tasked with a number of duties including: conservation of the surrounding landscape, coastal and meteorology surveillance, and search and rescue efforts.32

Keepers and their families were relatively isolated as the road to Sugarloaf Point was largely inaccessible. Once telegraph communications to the lighthouse were established in March 1877 however, a proper road was constructed from Bulahdelah out to the lighthouse.33

The jetty built during the construction of the lighthouse served as a lifeline to the keepers, as it enabled supplies to be delivered via boat, and also permitted traveller and school teachers to access to region.

As the decades progressed and domestic travel grew, tourists visited the lightstation and a small fishing village at Seal Rocks developed gradually from 1917 onwards.34

3.7 Chronology of major events

The following table details the major events to have occurred at Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse

Date | Event |

1 December 1875 | Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse lit for first time. |

8 August 1895 | The SS Catterthun wrecked on reef near Seal Rocks. 55 lives lost and 26 passengers rescued.35 |

10 July 1900 | Tower struck by lightning. Oil store blown up causing destruction of the electric bell installation.36 |

1901 | New stables, oil and paint store erected, and new lightning conductor installed. |

| Brewis visits and inspects lightstation. |

1966 | Keepers reduced from three to two. |

1997 | Lighthouse de-manned. |

2004 | Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse listed on Commonwealth Heritage List. |

December 2015 | Lighthouse opened to the public for 140th Anniversary. |

2019 | Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse listed on NSW State Heritage Register. |

3.8 Changes and conservation over time

The following section details the changes and conservation efforts to have been carried out at Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse since its construction.

The Brewis Report

Commander CRW Brewis, retired naval surveyor, was commissioned in 1911 by the Commonwealth Government to report on the condition of existing lights and to recommend any additional ones. Brewis visited every lighthouse in Australia between June and December 1912 and produced a series of reports published in their final form in March 1913. These reports were the basis for future decisions made in relation to the individual lighthouses and provide a snapshot of the lightstation in the early 20th century.

Brewis recommended that Sugarloaf Point’s subsidiary green light be discontinued.37

SUGARLOAF POINT LIGHT.

|

Alteration to the light

The following table details the changes to the Sugarloaf Point light since its exhibition in 1875.

Date | Alteration |

1911 | 55mm Schmidt-Ford IOV burner installed Intensity: 122,000 |

1 April 1923 | Lighthouse converted to incandescent vaporised kerosene burner. Intensity (white light): 174,000 candelas. |

14 June 1966 | Light converted to electric power with diesel backup. Ball bearing pedestal installed. Intensity (white light): 1,000,000 candelas Intensity (green light): 2,000 candelas |

6 December 1984 | Green subsidiary light changed to red. |

1987 | Light automated and keepers withdrawn. |

2016 | Light source changed to LED. |

For information on current light details, see ‘Appendix 4 Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse current light details’, and ‘Appendix 5 Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse auxiliary light details’.

Recent conservation works

At the time of preparing this management plan, no recent, major conservation works have occurred at Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse outside of general maintenance. This section will be updated in future versions of this plan.

3.9 Summary of current and former uses

From its construction in 1875, Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse has been used as a marine AtoN for mariners at sea. Its AtoN capability remains its primary use.

The lightstation complex consists of:

- The light tower

- Head Keeper’s quarters

- Assistant Keeper’s cottages

- Other buildings and elements including generator building, garage, paint storage shed, and signal house.

- Other features include the stone retaining walls at the cuttings for the Keepers’ Quarters buildings and the brick drainage gutters located on the levelling of the slope above, various timber fences including pickets, palings and railings, the signals mast and inclinator.

Approximately 32 hectares of crown land, including the Sugarloaf Point Lightstation, was added to Myall Lakes National Park in March 2003.

Plaques on the grassed slope east of the lighthouse record memorials to Tom Chalker, Head Lighthouse Keeper who passed away in 1997, Albert Stevens and Freya Girvin Sherriff.

Within the curtilage of the Commonwealth Heritage Listed place are the Lighthouse Tower and Signal House. The remaining buildings including the Keepers’ Cottages are important contribution to the understanding of the place but are not considered in this report as they lie outside the boundary of the Commonwealth Heritage listed place.

Figure 13. Grand plan of Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse site. Courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A9568, 1/16/6 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Figure 13. Grand plan of Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse site. Courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A9568, 1/16/6 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

3.10 Summary of past and present community associations

Aboriginal associations

The Myall National Parks holds immense significance to local Aboriginal parties who maintain strong connections to the landscape. This country contains a number of sites which continue to uphold strong connections to spirituality, ceremony and family. Further consultation with Traditional Stakeholders is required.

Local, national and international associations

Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse is considered a significant site of New South Wales and Australian history. The headland and lightstation maintain strong familial associations due to the lighthouse’s extensive history as a manned site. This is particularly notable due to the various memorials located onsite which assist cementing ties to the lightstation.

3.11 Unresolved questions or historical conflicts

The date that the lightstation was de-manned is contested. Searle determines that the lighthouse was officially de-manned in 1987, however some determine that the site was not officially de-manned until 1997.38 A caretaker resided at the lightstation following this period to carry out maintenance until NSW NPWS assumed full responsibility for the upkeep of the station.

3.12 Recommendations for further research

Further investigation into life at the lightstation during the late 19th century and early 20th century would provide greater insight into the social history of the lighthouse.

Footnotes

12 Garry Searle, First Order: Australia’s Highway of Lighthouses, (SA: Seaside Lights, 2013), 34.

13 Graham Brooks and Associates, NPWS Lighthouses Conservation Management and Cultural Tourism Plan: Supplementary Information for Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse (National Parks and Wildlife Service, 2004), 6.

14 Graham Brooks and Associates, NPWS Lighthouses Conservation Management and Cultural Tourism Plan¸ 6.

15 Graham Brooks and Associates, NPWS Lighthouses Conservation Management and Cultural Tourism Plan¸ 6.

16 It is understood that the survivors of the Mary-Ann shipwreck found the bodies of those killed in the Sally shipwreck. Graham Brooks and Associates, NPWS Lighthouses Conservation Management and Cultural Tourism Plan¸ 6.

17 Searle, First Order¸ 161.

18 Searle, First Order¸ 161.

18 Searle, First Order¸ 161.

20 Clive Lucas, Stapleton and Partners, Sugarloaf Point Lightstation Conservation Management Plan, 54.

21 Graham Brooks and Associates, NPWS Lighthouses Conservation Management and Cultural Tourism Plan¸ 7; Clive Lucas, Stapleton and Partners, Sugarloaf Point Lightstation Conservation Management Plan, 54; Searle, First Order¸ 162.

22 Clive Lucas, Stapleton and Partners, Sugarloaf Point Lightstation Conservation Management Plan, 54.

23 Clive Lucas, Stapleton and Partners, Sugarloaf Point Lightstation Conservation Management Plan, 55.

24 Clive Lucas, Stapleton and Partners, Sugarloaf Point Lightstation Conservation Management Plan, 55.

25 Graham Brooks and Associates, NPWS Lighthouses Conservation Management and Cultural Tourism Plan¸ 6.

26 Graham Brooks and Associates, NPWS Lighthouses Conservation Management and Cultural Tourism Plan¸ 7; Clive Lucas, Stapleton and Partners, Sugarloaf Point Lightstation Conservation Management Plan, 55-56.

27 Graham Brooks and Associates, NPWS Lighthouses Conservation Management and Cultural Tourism Plan¸ 8.

28 The camp and its buildings were removed by 1876. Graham Brooks and Associates, NPWS Lighthouses Conservation Management and Cultural Tourism Plan¸ 8.

29 Graham Brooks and Associates, NPWS Lighthouses Conservation Management and Cultural Tourism Plan¸ 8.

30 Graham Brooks and Associates, NPWS Lighthouses Conservation Management and Cultural Tourism Plan¸ 8.

31 Graham Brooks and Associates, NPWS Lighthouses Conservation Management and Cultural Tourism Plan¸ 8.

33 Graham Brooks and Associates, NPWS Lighthouses Conservation Management and Cultural Tourism Plan¸ 6.

34 Graham Brooks and Associates, NPWS Lighthouses Conservation Management and Cultural Tourism Plan¸ 6-7.

36 C.R.W. Brewis, Lighting of the East Coast of Australia: Cape Moreton to Gabo Island, Including coast of New South Wales (Victoria: Acting Government Printer, 1913), 52.

37 Graham Brooks and Associates, NPWS Lighthouses Conservation Management and Cultural Tourism Plan¸ 9.