3.1 General history of lighthouses in Australia

The first lighthouse to be constructed along Australian soil was Macquarie Lighthouse, located at the entrance to Port Jackson, NSW. First lit in 1818, the cost of the lighthouse was recovered through the introduction of a levy on shipping. This was instigated by Governor Lachlan Macquarie, who ordered and named the light.

The following century oversaw the construction of hundreds of lighthouses around the country. Constructing and maintaining a lighthouse were costly ventures that often required the financial support of multiple colonies. However, they were deemed necessary aids in assisting the safety of mariners at sea. Lighthouses were firstly managed by the colony they lay within, with each colony developing their own style of lighthouse and operational system. Following Federation in 1901, which saw the various colonies unite under one Commonwealth government, lighthouse management was transferred from state hands to the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service.3

3.2 Lamps and optics – an overview

Lighthouse technology has altered drastically over the centuries. Eighteenth century lighthouses were lit using parabolic mirrors and oil lamps.

Documentation of early examples of parabolic mirrors in the United Kingdom, circa 1760, were documented as consisting of wood and lined with pieces of looking glass or plates of tin. As described by Searle, “When light hits a shiny surface, it is reflected at an angle equal to that at which it hit. With a light source is placed in the focal point of a parabolic reflector, the light rays are reflected parallel to one another, producing a concentrated beam”4.

In 1822, Augustin Fresnel invented the dioptric glass lens. By crafting concentric annular rings with a convex lens, Fresnel had discovered a method of reducing the amount of light absorbed by a lens. The Dioptric System was adopted quickly with Cordouran Lighthouse (France), which was fitted with the first dioptric lens in 1823. The majority of heritage-listed lighthouses in Australia house dioptric lenses made by others such as Chance Brothers (United Kingdom), Henry-LePaute (France), Barbier, Bernard & Turenne (BBT, France) and Svenska Aktiebolaget Gasaccumulator (AGA of Sweden). These lenses were made in a range of standard sizes, called orders—see ‘Appendix 2. Glossary of lighthouse Terms relevant to Montague Island Lighthouse’.

Early Australian lighthouses were originally fuelled by whale oil and burned in Argand lamps, and multiple wicks were required in order to create a large flame that could be observed from sea. By the 1850s, whale oil had been replaced by colza oil, which was in turn replaced by kerosene, a mineral oil.

In 1900, incandescent burners were introduced. This saw the burning of fuel inside an incandescent mantle which produced a brighter light with less fuel within a smaller volume. Light keepers were required to maintain pressure to the burner by manually pumping a handle as can be seen in Figure 12.

In 1912, Swedish engineer Gustaf Dalén, was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for a series of inventions relating to acetylene-powered navigation lights. Dalén’s system included the sun valve, the mixer, the flasher, and the cylinder containing compressed acetylene. Due to their efficiency and reliability, Dalén’s inventions led to the gradual demanning of lighthouses. Acetylene was quickly adopted by the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service from 1915 onwards.

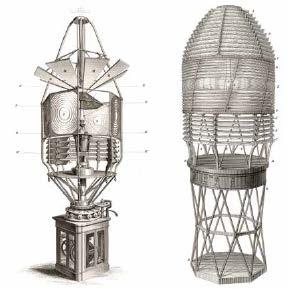

Large dioptric lenses, such as that shown in Figure 13, gradually decreased in popularity due to cost and the move towards unmanned automatic lighthouses.

Figure 13. Dioptric lens on display at Narooma

By the early 1900s, Australia had stopped ordering these lenses with the last installed at Eclipse Island in Western Australia in 1927.

Smaller Fresnel lenses continued to be produced and installed until the 1970s when plastic lanterns, still utilising Fresnel’s technology, were favoured instead. Acetylene remained in use until it was finally phased out in the 1990s.

Figure 14. Dalén’s system – sunvalve, mixer, flasher and cylinder

Figure 14. Dalén’s system – sunvalve, mixer, flasher and cylinder

3.2 The Commonwealth lighthouse service

When the Australian colonies federated in 1901, it was decided that the new Commonwealth Government would be responsible for coastal lighthouses. This included only the major lights used by vessels travelling from port to port, not the minor lights used for navigation within harbours and rivers. There was a delay before this new arrangement came into effect and the existing lights continued to be operated by the states.

Since 1915, various Commonwealth departments have managed lighthouses. The Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA), established under the Australian Maritime Safety Authority Act 1990, is now responsible for operating Commonwealth lighthouses and other marine aids to navigation, along with its other functions.

3.3 New South Wales lighthouse service administration

The table below details the timeline of lighthouse service administration from 1915 to present.

| Time period | Administration |

|---|---|

| 1915 – 1927 | Lighthouse Branch No. 3 District New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania, Sydney headquarters. |

| 1927 – 1963 | Deputy Director of Lighthouses and Navigation, New South Wales. |

| 1963 – 1972 | Department of Shipping and Transport, Regional Controller, New South Wales. |

| 1972 – 1977 | Department of Transport , New South Wales Region / (from 1973) Surface Transport Group, New South Wales region. |

| 1977 – 1982 | Department of Transport , New South Wales region. |

| 1982 – 1983 | Department of Transport and Construction, regional office, New South Wales. |

| 1983 – 1987 | Department of Transport , New South Wales regional office. |

| 1987 – 1990 | Department of Transport and Communications (Transport Group), New South Wales regional office. |

| 1991 – | Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA). |

3.4 Montague Island: a history

Indigenous history

Vivienne Mason, Chairperson of Wagonga Local Aboriginal Land Council, Elder and Knowledge Holder of the Yuin Tribe shared knowledge of the land the light house sits on:

“A Dreamtime Story of my people, the Yuin, is that Barranguba (Montague Island) is the son of Gulaga, the mother mountain, (Mt Dromedary). Barranguba being the eldest son wanted to leave his mother, Gulaga. Gulaga agreed that Barranguba could move, but only on the condition that she would be able to watch over him. Barranguba went off-shore to live, far enough away from his mother but close enough for her to watch over him. Gulaga’s youngest son, Nadjanuka also wanted to leave but Gulaga insisted he stayed close by on the land to protect the Budjarns (Birds). To this day Barranguba, Nadjanuka and Gulaga are connected through her umbilical cord (an Underwater Freshwater Stream running from Gulaga to Barranguba and Nadjanuka. There is a fresh water spring on Barranguba but the location has been lost.”

‘Also, we were told, many years ago, that Aboriginal paintings were found on Barranguba, but they are now hidden due to the changes to the land. Legend has it that Barranguba is a Men’s Place but this is debated, it depend on who you speak to.”

It is recorded in a newspaper article from the first settlers of Narooma (copy at the National Library), that a tragedy befell a group of young Aboriginal men and women, who were returning from their annual seabird egg gathering expedition from Barranguba. These young people were lost at sea when a freak wave hit them.

Early European history

In 1770, British navigator and cartographer James Cook sailed along the New South Wales coast. Although recording the ‘camel-shaped mountain’ which he named Mount Dromedary, Cook did not recognise the island as separate to the mainland and mistakenly recorded it as part of the headland.

It was not until 1790 that the convict ship Surprise determined Montague was in fact an island. It is alleged the island was named after George Montague Dunk, the Earl of Halifax.

Research on the early European history of the island yielded little information. During the mid-19th century, a gold rush occured in Nerrigundah, north of Narooma, and it is alleged sea bird eggs were collected from Montague to sell to the miners. Records indicate a number of fishing shacks existed at some point on the western shore of the island, however no substantial structures were built and no remains have been located.9

3.5 Planning a lighthouse

Why Montague Island?

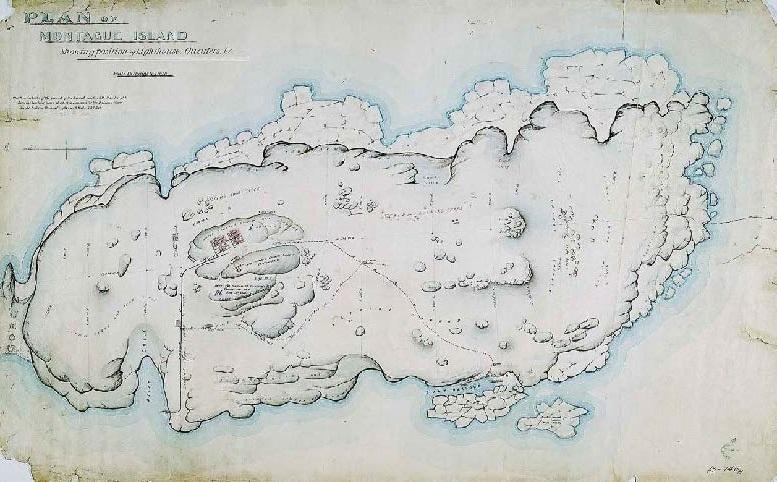

Due to its offshore and elevated position, Montague Island offered the perfect vantage point for a light.

In 1873, the erection of a lighthouse on Montague Island (known then as Montagu) was first proposed during a conference between the principal officers of the Marine Departments of the Australian Colonies chaired by Captain Hixson. However, it was not until 1877 that funds were allocated by the New South Wales Government to carry out the project.10

Design

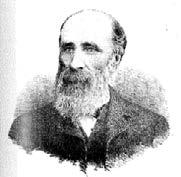

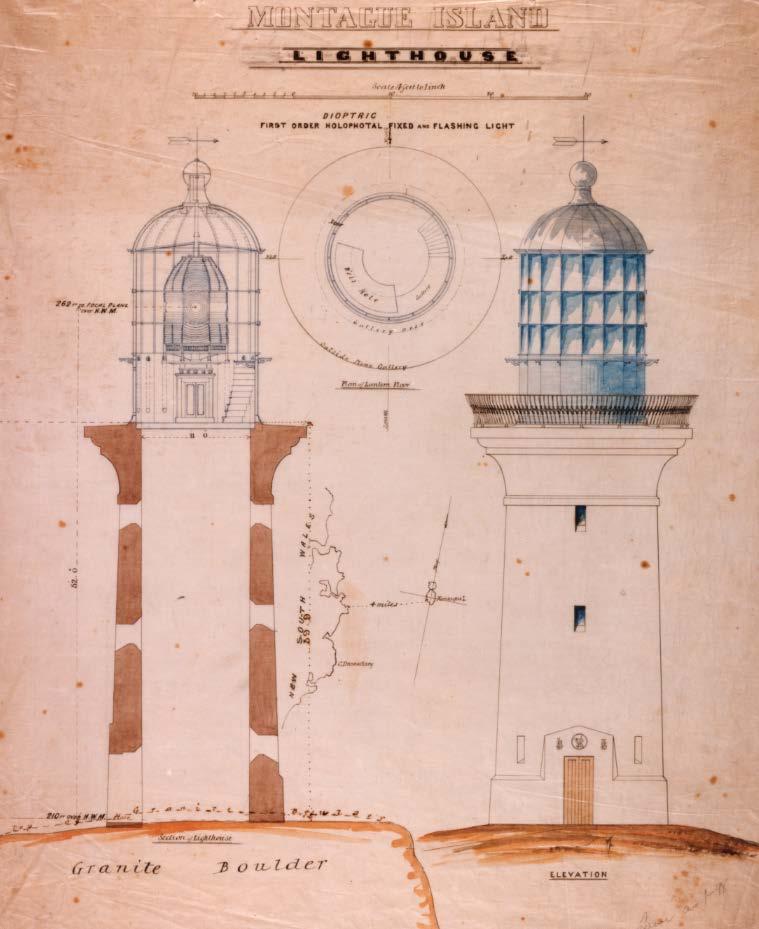

James Barnet, colonial architect for New South Wales, was placed in charge of designing the plans for a light at Montague Island. Barnet, alongside prospective tenders, visited the Island and assisted in selecting the best location for a lightstation. His blueprints, which were created following this visit, featured a granite tower 12-m in height with tapering walls and one upper platform.

James Barnet (1827-1904)

Born 1827, Barnet studied drawing, design and architecture in London before he and his family migrated to Australia c.1854. Appointed Clerk of Works for Sydney University, Barnet later joined the Colonial Architect’s Office in 1860. By 1865, he was named Colonial Architect, a position he held until his retirement in 1890. In that timeframe, Barnet was responsible for the architectural design of numerous public works including allegedly 15 lighthouses. His design style, adopted from Francis Greenway’s Macquarie Light (1818), served as the quintessential NSW style until the end of the 19th century.

Construction

Tenders for the construction of a light at Montague Island were called October 1878. The initial successful contractor, J Musson and Co., had their offer of £13,900 accepted for an estimated 15-month construction period. The contract was signed on the 5 February 1879.

Work commenced with Mr John Kelly acting as foreman of works on behalf of the government, and Mr James Peters for the contractors. However, poor management and inadequate materials hindered work running smoothly onsite. The lighthouse was to stand on a large boulder overlooking the Island, and Barnet strictly instructed the boulder not to be touched. Contrary to these express orders, the contractor fired a shot at the boulder which detached a large mass and caused the position of the Tower to be altered by several feet. Following this, J Musson and Co. gave up the contract. Tenders were called once more in July of 1879, however no successful contracts were secured.11

Fresh tenders were called again in 1880 following renewed interest from the government and WH Jennings was deemed the successful contractor for £16,950. On Barnet’s blueprints for the tower, (See Figure 17) the names of the original contractors can be seen crossed out and replaced by WH Jennings. The foundation stone was laid on St Patricks Day 1881. Jennings recorded the progress of the construction:

The top of the island, in the neighbourhood of the lighthouse and keepers’ quarters, presents a busy appearance. Every available piece of ground at all level is occupied by masons, carpenters, plasterers, plumbers, blacksmiths, and their assistants. There is a tramway from the site of the buildings to the landing place, where a powerful crane is fixed, and moorings are made fast to the rocks and to buoys which are secured by heavy anchors in the sea. The landing of goods and materials is done quickly, 60,000 bricks, 100 casks cement, and 75 sheep having been landed in less than 24 hours. The lighthouse will be a solid and elegant structure….

…..[the walls are] 3 feet 8 inches thick at base, tapering to 2 feet 2 inches….

…..the quarters will accommodate three keepers…. 12

Work was carried out effectively and the lighthouse was completed in October 1881, four months within the contract time. The overall cost of the construction, including apparatus, amounted to £25,981 following completion.

Figure 16. Montague Island Lighthouse first order dioptric holophotal fixed and flashing light (1878)

Figure 16. Montague Island Lighthouse first order dioptric holophotal fixed and flashing light (1878)

Figure 18. Montague Island Lighthouse site plan (James Barnet, 1878)

Figure 18. Montague Island Lighthouse site plan (James Barnet, 1878)

Equipment when built

Following construction, Montague lighthouse stood as a 21 m tall circular granite tower with a light source powered by kerosene, providing an intensity of 45,000 cd.

The 910 mm focal radius, 8 panels, 1st Order Chance Bros. lantern and lens rotated on a roller pedestal which operated by clockwork mechanism and weights in the central tube within the tower.

The lens revolved every four minutes with:

“a steady flare for 30 seconds, then an eclipse for 13 seconds, and then a brilliant flash lasting four seconds, followed by another eclipse of 13 seconds’ duration.” 13

3.6 Lighthouse keepers

Due to the island’s isolation, lightkeeping was a demanding livelihood. The arrival of food and supplies from passing steamers lay at the mercy of the weather and swell of the surrounding waters. In 1952, the lightkeepers and their families went without fresh food for 10 days, eventually resorting to hunting wild goats roaming the Island. 14

Tragedy was also a common theme on the island. The lack of medical assistance available, and the inability to traverse the passage separating the island from the mainland, meant deaths among lightkeepers and their families occured. Head keeper, John Burgess, lost two of his children in the 1880s, one to whooping cough and the other to an unknown illness, and an assistant keeper Charles Townsend died after being thrown from his horse in 1894.

Mrs John Burgess’s letter to the local newspapers exemplified the consequences of isolation in 1894:

I have been a lighthouse keeper’s wife for nearly fifteen years, both at South Solitary and Montague Islands. During that period several deaths have occurred in my family and those of the assistants, also accidents. We never could procure assistance till too late; although steamers pass both north and south frequently, they do not seem to see when we have a distress signal flying from our flagstaff. 15

The graves of the Burgess children and Mr Townsend, which are located nearby the lighthouse and cottages, are a stark reminder of the dangers faced in taking up lightkeeping in isolated locations.16

The move to automate the lighthouse in the 1980s faced controversy among keepers and local communities who feared it would lead to its dilapidation.17

Eventually however, the lighthouse was officially de-manned in 1986 following the station’s automation.

3.7 Chronology of major events

The table below details the major events to have occurred at the Montague Island Lightstation.

| Date | Event Details |

|---|---|

| 1881 | The Montague Island Lighthouse officially lit for the first time. |

| 3 Dec 1894 | Assistant lightkeeper, Mr Townsend, killed in cart accident on Montague Island. |

| 13 Dec 1894 | Light keeper, Mr Emanuel Francis, wounded in an accident involving a burst gun on Montague Island. Francis had only recently arrived on the island to replace the previous assistant lightkeeper, the late Mr Townsend, who had been killed the week before.18 |

| 5 Aug 1895 | Tremors experienced at Montague Island Lighthouse – no damage to lighthouse.19 |

| Sep 1907 | First scientific visit conducted on the island by ornithologist, AF Basset Hull. |

| Apr 1908 | The Department of Navigation received word from the Montague Island Lighthouse that owing to a strike, no supply vessels had delivered food to the lighthouse for over a fortnight.20 |

| Mar 1910 | Acetylene gas Morse signal lamp installed on Montague Island – allowing improved communication with Pilot Station in Narooma. |

| 1938-39 | Transceiver radio telephone outfits installed at Montague Island Lighthouse. 21 |

| Circa 1930s-1940s | The island used as a defence facility by the Royal Australian Navy. |

| 1952 | Cyclones leave lightkeepers marooned without supplies on Montague Island.22 RAAF parachutes food on island for keepers.19 |

| 1953 | Montague Island named a wildlife sanctuary under the control of the National Trust of Australia (NSW) |

| 21 Oct 1980 | Montague Island Lighthouse included on the Register of the National Estate. |

| 11 Mar 1983 | Public meeting held to discuss the government’s proposal to automate the Montague Island Lighthouse.23 |

| 14 Sept 1986 | First order lens turned off and removed to mainland. Lighthouse officially de-manned. |

| 1987-89 | Management of the island transferred to NPWS. The Department of Transport retained the lighthouse tower and continued its operation as an AtoN.24 |

| 16 Dec 1989 | The first day tours to the island permitted. |

| 17 Jan 1990 | Montague Island named a nature reserve. |

| 1993 | NPWS begins $180,000 project to conserve the Montague Island Lighthouse precinct.25 |

| 1999 | Montague Island Lightstation listed on the NSW Heritage Register. |

| 22 June 2004 | Montague Island Lighthouse included on the Commonwealth Heritage List |

3.8 Changes and conservation over time

The Montague Island Lighthouse has undergone minimal changes since its construction in 1901. Changes that have been made were largely in relation to the light source and electrical systems. The following sections detail the changes made to the lightstation.

The Brewis Report (1913)

In 1911, Commander CRW Brewis, retired naval surveyor, was commissioned by the Commonwealth Government to report on the condition of existing lights and to recommend any additional ones.

Brewis visited every lighthouse in Australia between June and December 1912 and produced a series of reports published in their final form in March 1913. These reports were the basis for future decisions.

Brewis’ recommendations for Montague Island included changing the character of the light, inserting a new clockwork mechanism and pedestal and installing new wireless telegraph equipment.

Brewis Report: Montagu Island Light 28

25 miles from Burrewarra Point, 73 miles from Perpendicular Head.

Lat. 36º 15’S., Long. 150º 14’E., Chart No. 1018. – Established 1880. Last altered 1910.

Character – Main Light: One white, dioptric. Fixed and flashing every 70 seconds, thus:-Flash, 5 seconds; eclipse, 16 seconds; fixed, 33 seconds; eclipse, 16 seconds. Candle-power: Flashing, about 45,000; fixed, 7,500 c.p. Illuminant, vaporized kerosene; 55 mm. mantle.

Circular grey granite tower, 53 feet. Height of focal plane, 262 feet.

Visibility: In clear weather, all round the horizon, for a distance of about 20 nautical miles.

Optical Apparatus: Chance Bros., 1879. Eight panels. Focal radius, 36 inches. One revolution every 4 minutes 40 seconds.

Condition and State of Efficacy: The tower, lantern, optical apparatus, and dwellings are in good condition.

The light is too slow for modern requirements.

Three light-keepers are stationed here.

Communication: Provisions and mails once weekly by coastal steamer. Government stores yearly. The lighthouse is not connected by telephone with the mainland, but messages by distant signals during the day and by Morse lamp at night may, under favourable conditions, be sent and received via the signal station at Narooma (distant 5 miles), which has telephonic communication with the main telegraph system.

Electric Morse lamp at lighthouse.

Fogs: From January to March, fogs may be experienced and may last as long as nine hours.

Soundings: From 5 miles off Thubbul River to about 1 mile westward of Montagu Island, this soundings range from 51 to 17 fathoms on a sandy bottom, but at 7 miles south-eastward of the island there is no bottom at 100 fathoms.

RECOMMENDED:

(a) The speed of the flashes be increased by inserting new mechanism (pedestal and clock), so as to give one revolution every 80 seconds, and produce a character of fixed and flashing every 20 seconds, thus: Fixed, 9 ½ seconds; eclipse, 4 ½ seconds; flash, 1 ½ seconds; flash, 1 ½ seconds; eclipse, 4 ½ seconds.

(b) Wireless telegraph equipment be installed. Nearest main wireless station, Gabo Island, distant about 84 miles.

Alterations to the Light

Due to developments in technology, the Montague Island Lighthouse was modified multiple times to improve its use as an AtoN.

| Date | Alteration |

|---|---|

| 1910 | 55 mm Schmidt-Ford vaporised kerosene powered mantle installed. Intensity: 250,000 candlepower (cp) |

| 13 April 1923 | New mantle installed. Intensity: 357,000 cp |

| 19 July 1926 | Roller pedestal removed. Mercury bath pedestal installed. Four of the original eight panels screened off – light now only produces a flashing light. |

| 20 June 1969 | Conversion to diesel electric operation – 1000 W Tungsten-halogen lamp installed. Four optic panels (ex-Green Cape lighthouse) installed. Intensity: 1,000,000 cp |

| 14 Sept 1986 | First order lens turned off and removed to the mainland. |

| 28 Nov 1986 | Solar-powered PRP-24 beacon installed. Lighthouse fully-automated. |

| 6 April 2006 | Solar-powered Vega VRB-25 beacon installed. Intensity: 132,736 cp |

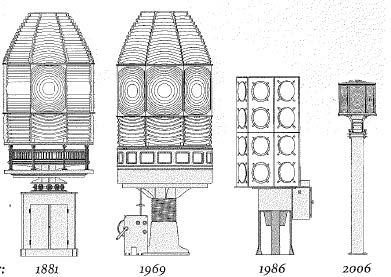

Figure 20. Evolution of Montague Island Lighthouse lens/lanterns (Searle, 2013, pg. 209)

Figure 20. Evolution of Montague Island Lighthouse lens/lanterns (Searle, 2013, pg. 209)

Conservation Works

The table below details the major rectification works carried out on the Montague Island Lighthouse.These works have been undertaken as proactive measures to preserve the tower’s fabric and materials.

| Date | Works completed |

|---|---|

| Circa 1980s | Lantern room refurbished |

| Sept 1986 | Original lantern and lens removed from tower |

3.9 Summary of current and former uses

From its construction in 1881, the Montague Island Lighthouse has been used as a marine AtoN. Its AtoN capabilities remain its primary use.

The Montague Island Lighthouse as a key tourism site developed over recent decades following the transferral of the Island to the NPWS, and the keepers’ cottages are now used for tourist accommodation.

The Montague Island Lightstation precint is now used:

- to house NPWS staff stationed on the island, as well as accommodating researchers and tour guides

- a key tourism site, with facilities.

3.10 Summary of past and present community associations

Aboriginal associations The Wagonga Local Aboriginal Land Council shared with AMSA the following:

“The language spoken is Dhurga. Both Walbunja Yuin and Djirridjan Yuin claim connection to Barranguba. Please note that all Yuin people have a connection to Barranguba, Nadjanuka and Gulaga as they forever protect their people.

Today our people are restricted from accessing our special places which is due to white man’s laws and regulations.”

AMSA is currently working to erect a symbol on the island to acknowledge the Yuin people’s Elders, past, present and future generation.

Local, National, and International associations

Montague Island maintains firm state and national associations owing to its standing as a nature reserve under the NPWS. Montague Island Nature Reserve hosts one of the longest running seabird research programs in the world. This, combined with the unique species present, the accessibility of the island and its geographical location and significant size highlights the importance of Montague Island ecologically and scientifically. The nature reserve offers a protective sanctuary to species of local and national concern.

The lighthouse itself maintains strong associations with past lighthouse keeping families owing to the significant period of time the lightstation was manned.

3.11 Unresolved questions or historical conflicts

A number of dates are disputed amongst past research.

The year the lighthouse was de-manned is disputed. Some sources credit 1985, others credit 1986. There is also uncertainty over which year the island was handed over to the NPWS with sources citing 1987-89.

Despite much of its history being recorded, information on the lighthouse keepers of Montague Island is relatively limited. The list of names and years of service is incomplete and very little is known about the majority of those that occupied the site for more than 80 years.

3.12 Recommendations for further research

Archaeological investigation of the site may reveal further information on prehistoric and historic uses of Montague Island to broaden understandings of the site’s intrinsic value.

Footnotes

3. Figure 11 – Early example of a rotating catadioptric apparatus, made for the 1844 lighthouse at Skerryvore, Western Scotland (Steel engraving from Tomlinson’s Cyclopaedia of Useful Arts, 1854)

4. Searle. G, First Order: Australia’s Highway of Lighthouses, (2013). Page 34.

9. Brooks, G., and Assoc. NPWS Lighthouses (2001), pg. 4.

10. Brooks, G., Assoc. NPWS Lighthouses (2001), pg. 4.

11. Searle, G., First Order (2013), pg. 203.

12. Quoted in Searle, G., First Order (2013), pg. 203.

13 Quoted in Searle, G., First Order (2013), pg. 205.

14. Searle, G., First Order (2013), pg. 204-205.

15. “Shipping: Montague Island,” Evening News, Dec 19, 1894

16. Searle, G., First Order (2013), pg. 205.

17. “Island’s future threatened by automation,” The Canberra Times, Jan 7, 1983

18. “Fatal accident at Montagu Island,” The Daily Telegraph, Dec 10, 1894

19. “The Montague Island Lighthouse: Another Accident,” The Daily Telegraph, Dec 14, 1894

20. “Earthquake at Montague Island,” The Daily Telegraph, Aug 6, 1895

21. “In urgent need of food: A message from Montague Island,” The Daily Telegraph, Apr 8, 1908

22. “Lighthouse Radios,” The Argus, Oct 28, 1938

23. “Lighthouse families marooned,” The Newcastle Sun, Aug 7, 1952

24. “R.A.A.F. parachutes food on Montague Island,” The Canberra Times, Aug 9, 1952

25. “Meeting to discuss lighthouse plans,” The Canberra Times, Feb 27, 1983

26. “Montague Island wildlife haven,” The Canberra Times, Sept 20, 1992

27. “Old lighthouse,” The Canberra Times, Jan 28, 1993

28. CRW Brewis, Lighting of the East Coast of Australia: Cape Moreton to Gabo Island Including Coast of New South Wales (1913), pg. 21.