3.1 General history of lighthouses in Australia

The first lighthouse to be constructed on Australian soil was Macquarie Lighthouse, located at the entrance to Port Jackson, NSW. First lit in 1818, the cost of the lighthouse was recovered through the introduction of a levy on shipping. This was instigated by Governor Lachlan Macquarie, who ordered and named the light.

The following century oversaw the construction of hundreds of lighthouses around the country. Constructing and maintaining a lighthouse were costly ventures that often required the financial support of multiple colonies. However, they were deemed necessary aids in assisting the safety of mariners at sea. Lighthouses were firstly managed by the colony they lay within, with each colony developing their own style of lighthouse and operational system. Following Federation in 1901, which saw the various colonies unite under one Commonwealth government, lighthouse management was transferred from state hands to the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service.

Lamps and optics: an overview

Lighthouse technology has altered drastically over the centuries. Eighteenth century lighthouses were lit using parabolic mirrors and oil lamps. Documentation of early examples of parabolic mirrors in the United Kingdom, circa 1760, were documented as consisting of wood and lined with pieces of looking glass or plates of tin. As described by Searle, “When light hits a shiny surface, it is reflected at an angle equal to that at which it hit. With a light source is placed in the focal point of a parabolic reflector, the light rays are reflected parallel to one another, producing a concentrated beam”.10

In 1822, Augustin Fresnel invented the dioptric glass lens. By crafting concentric annular rings with a convex lens, Fresnel had discovered a method of reducing the amount of light absorbed by a lens. The Dioptric System was adopted quickly with Cordouran Lighthouse (France), which was fitted with the first dioptric lens in 1823. The majority of heritage-listed lighthouses in Australia house dioptric lenses made by others such as Chance Brothers (United Kingdom), Henry-LePaute (France), Barbier, Bernard & Turenne (BBT, France) and Svenska Aktiebolaget Gasaccumulator (AGA of Sweden). These lenses were made in a range of standard sizes, called orders—see ‘Appendix 2. Glossary of lighthouse Terms relevant to Cape du Couedic Lighthouse’.

|

|

Early Australian lighthouses were originally fuelled by whale oil and burned in Argand lamps, and multiple wicks were required in order to create a large flame that could be observed from sea. By the 1850s, whale oil had been replaced by colza oil, which was in turn replaced by kerosene, a mineral oil.

In 1900, incandescent burners were introduced. This saw the burning of fuel inside an incandescent mantle which produced a brighter light with less fuel within a smaller volume. Light keepers were required to maintain pressure to the burner by manually pumping a handle as can be seen in Figure 8.

In 1912, Swedish engineer Gustaf Dalén, was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for a series of inventions relating to acetylene-powered navigation lights. Dalén’s system included the sun valve, the mixer, the flasher, and the cylinder containing compressed acetylene. Due to their efficiency and reliability, Dalén’s inventions led to the gradual destaffing of lighthouses. Acetylene was quickly adopted by the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service from 1915 onwards.

Large dioptric lenses, such as that shown in Figure 9, gradually decreased in popularity due to cost and the move towards unmanned automatic lighthouses. By the early 1900s, Australia had stopped ordering these lenses with the last installed at Eclipse Island in Western Australia in 1927. Smaller Fresnel lenses continued to be produced and installed until the 1970s when plastic lanterns, still utilising Fresnel’s technology, were favoured instead. Acetylene remained in use until it was finally phased out in the 1990s.

In the current day, Australian lighthouses are lit and extinguished automatically using mains power, diesel generators, and solar-voltaic systems.

3.2 The Commonwealth Lighthouse Service

When the Australian colonies federated in 1901, they decided that the new Commonwealth government would be responsible for coastal lighthouses—that is, major lights used by vessels travelling from port to port—but not the minor lights used for navigation within harbours and rivers. There was a delay before this new arrangement came into effect. Existing lights continued to be operated by the states.

Since 1915, various Commonwealth departments have managed lighthouses. AMSA, established under the Australian Maritime Safety Authority Act 1990 (Cth), is now responsible for operating Commonwealth lighthouses and other aids to navigation, along with its other functions.

3.3 Cape du Couedic: a history

Aboriginal history

Kangaroo Island has an extensive history, and the island is embedded in the Ngurunderi Dreaming Story.

Ngurunderi, an ancestral being, chased two of his wives along the coastline of Encounter Bay. When they tried to cross the waters to Kangaroo Island, Ngurunderi made the ocean rise and flood what is now known as Backstairs Passage. His wives were drowned and became the Pages Islands. Ngurunderi then travelled to Kangaroo Island where, at the far end of the island at Admiral’s Arch, he threw his spears down into the sea which created the Casuarina Islets. Ngurunderi then cleansed himself in the ocean before passing into the spirit world.

More than 100 cultural heritage sites, which include stone artefact scatters, have been uncovered on the island, and radiocarbon dating undertaken on the western end of the island demonstrated the presence of Aboriginal groups for thousands of years.

Sally, also known as Kalinga and Princess Con, is a notable figure in the history of the island. Sally was the daughter of King Condoy, the headman of Ramindjeri. In the late 1820s, Sally was taken from her home in Cape Jervis by sealers to King George Sound, and then onto Kangaroo Island by the early 1830s. She later married William Walker and had two sons, George and Joseph who were both born on the island.

Early European history

Kangaroo Island was first sighted by British explorer Matthew Flinders aboard the HMS Investigator on 23 March 1802. Flinders had landed on the north coast of Dudley Peninsula and, after noting the large number of western grey kangaroo present, named the landmass ‘Kangaroo Island’.11 The island was circumnavigated and mapped by French explorer Commander Nicolas Baudin’s party aboard the Le Geographe, and the Le Casurina where the south coast was surveyed. The cape was named after celebrated French captain Charles Louis Chevalier du Couedic de Kergoualer, however some maps erroneously spelt it as Cape du Couedie which was not rectified until 1905.12

In 1836, the First Fleet of South Australia reportedly stopped in at the island’s Nepean Bay en route to the mainland. These ships, such as the Duke of York, the Lady Mary Pelham, and the Africaine, carried the first European settlers that would establish the city of Adelaide and the colony of South Australia. The first colonial settlement on Kangaroo Island was Kingscote (originally Reeves Point) established in July 1836.13

The 1840s saw the operation of whaling stations on the island’s coastline. Shipping around Kangaroo Island also grew exponentially during this time period as the island sat on either side of the Backstairs Passage and the Investigator Strait, two key shipping routes. Increased shipping led to many instances of shipwrecks around the island, which in turn led to the construction of lighthouses: Cape Willoughby in 1852 and Cape Borda in 1858.

3.4 Why Cape du Couedic?

Up until 1909, vessels travelling from the western Australian coastline to the eastern colonies were left blind until reaching Cape Borda Lighthouse on the north-western coast of Kangaroo Island. However, the light from Cape Borda was often obscured from the view of ships traversing waters close to the island if carried in strong currents too far south.14 The consequence of this was reflected in the loss of both ships and life.

By the end of the 19th century, a number of vessels had been lost in the waters by the island. In 1877, the Emily Smith was wrecked in the vicinity with a loss of life, and the Mars was wrecked in 1885 with eight lives lost.15 However the largest disaster occurred on 24 April 1899, when the Loch Sloy was wrecked on breakers by the island. 31 lives were lost, with four men managing to swim to shore. Three of the men were able to make it to nearby civilisations, however one man perished.16

Public outrage ensued following the wrecking, and the government was criticised for a lack of consideration for sailors traversing a dangerous coast. In the months following the loss of the Loch Sloy, the Marine Board consulted with mariners, presenting to them two possible positions for a light: South Neptune Island and Cape du Couedic. Of the two, South Neptune Island was favoured by the mariners as it was determined that a light on this position would assist vessels carried by an easterly current to a position where the Cape Borda light was obscured by cliffs.17 However, Captain P. Weir of Adelaide argued the following:

‘The south side of Kangaroo Island is, however, exceedingly dangerous by reason of the rocky coast and the reefs which abound, and is without a single lighthouse to warn mariners of their danger….Had this lighthouse [Cape du Couedic] been in existence the Loch Sloy would probably have been afloat to-day, and many lives would have been spared.’ 18

No immediate action was taken following these discussions, and in 1905, the Loch Vennachar was wrecked between Cape Borda and Cape du Couedic. Twenty-six lives were lost, and the government faced increasing pressure for a lighthouse to be constructed.19 Finally, Cape du Couedic was chosen as the site.

3.5 Building a lighthouse

Design

The original designs of the proposed Cape du Couedic Lighthouse were created by Mr J.B. Labatt, Assistant Engineer of Harbours, and included a sandstone tower with concrete balcony and staircase.20 The ground floor design also depicted two front doors, an inner and outer door. The purpose of this design was to ensure winds from the lighthouse would not impact the two sector lights located on the ground floor. Only one set of doors were permitted open at any one time.21

Construction

Workmen first arrived on Kangaroo Island on 4 October 1907, and a jetty at Weir’s Cove approximately one kilometre from site was the first structure to be built. These works were overseen by Inspector G. Wisdom. Initially, materials for the station were carted up a zig-zag path up the cliffs before a flying fox was constructed, enabling materials to be towed up the cliff instead.22

The works on the lightstation were overseen by Labatt and a Mr Lucas. Sandstone for the tower and cottages were quarried locally, and by early 1909, despite battling the elements on an exposed site, the construction of the tower was well underway. Three cottages were constructed of sandstone, and positioned in a low-lying area so as to reduce the impact from the winds on the cape.23

Captain Weir suggested a temporary light be exhibited throughout the duration of the construction, and the masthead light from Weir’s ship, the Governor Musgrave, was installed onsite and maintained by the workmen.

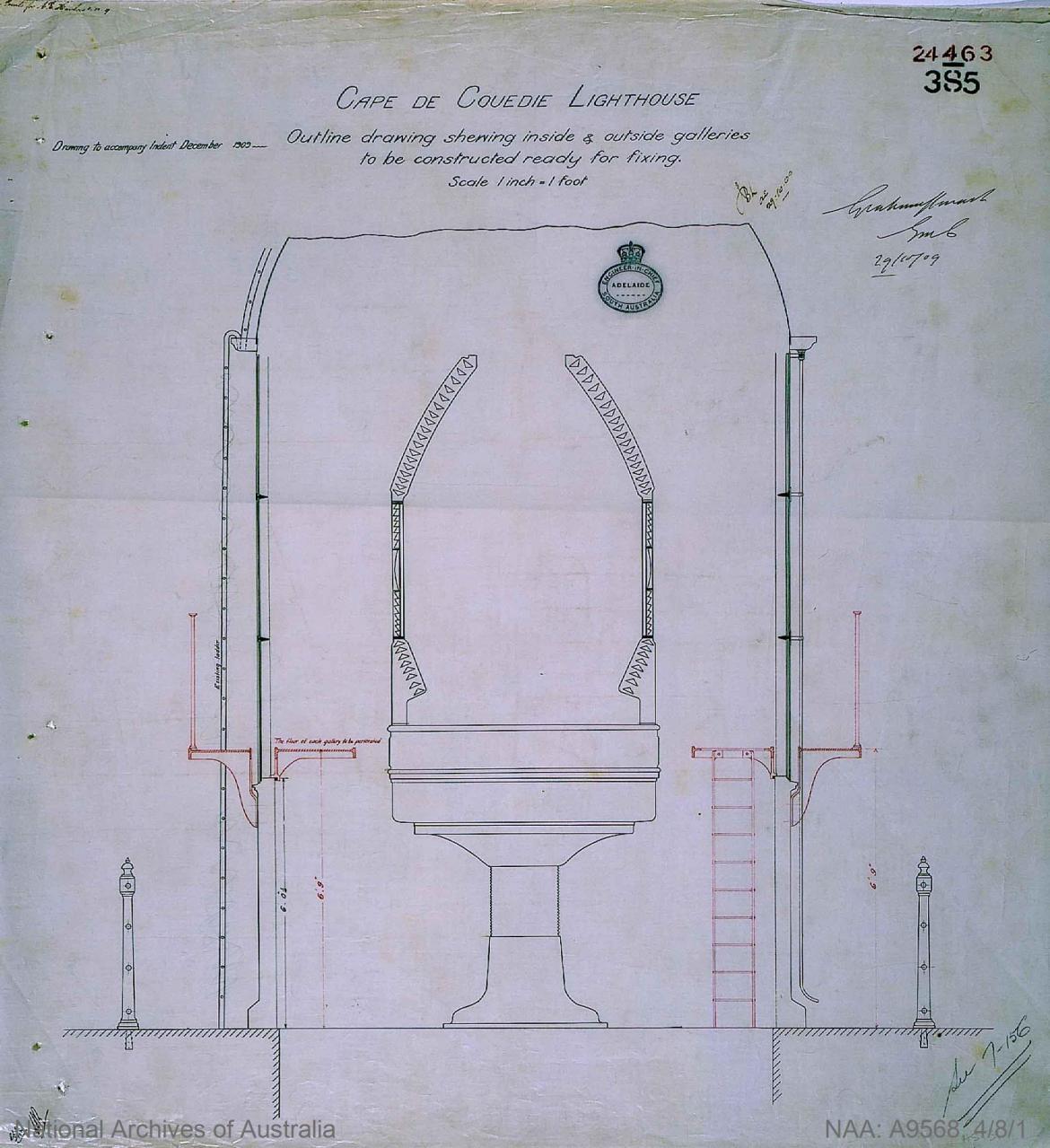

In the tower itself, two sector lights, one red, one white, were installed in order to warn vessels of the nearby Lipsons Reef and Casuarina Islands. A 12’9” Chance Bros. lantern was constructed at the top of the sandstone tower, and a 1st Order 6 panel lens installed.

Figure 12. Cape du Couedic Lighthouse: Outline drawing showing inside and outside galleries to be constructed ready for fixing, 1909. Image courtesy of the NAA: A9568, 4/8/1 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)24

Equipment when built

The Cape du Couedic light was first exhibited on 27 June 1909. The event was attended by members of the Marine Board including the President Mr Arthur. Labatt was also present at the event, however inclement weather forbade members from disembarking. When the light was lit for the first time by the keepers, the Marine Board members watched from the Governor Musgrave captained by Weir. The event was therefore considered a ‘keen disappointment’.25

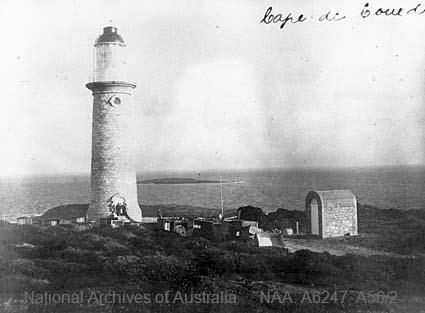

The lighthouse stood as a 17 metre sandstone tower with a red and white Chance Bros. lantern. Although records determined the tower was painted with red and white bands, it is believed the tower was bare sandstone as found at the site today.26 It was reported in the ‘Notice to Mariners’ that the light was double-flashing, with each flash lasting for 7.5 seconds, and an eclipse of 0.33 seconds. The tower was accompanied by the three sandstone keepers’ cottages which was approximately 160 metres from the lighthouse. It is believed the total cost of the lightstation was around £16,000.27

Light keeping

The first keepers to be stationed at Cape du Couedic were Mr. G.G. Duthie as Headkeeper, Mr G. E. Luckett as second-keeper, and Mr G. Marment as third-keeper. All three men were described as coming from experienced lightkeeping backgrounds, Duthie had previously been stationed at Troubridge Shoal, and Luckett had worked at Cape Northumberland Lighthouse prior to his posting at Cape du Couedic.28 Despite this experienced team, life at the station was not without peril. In 1910, just 13 months after Cape du Couedic was first lit, third keeper Marment was drowned near South Neptune Island while fishing.29

Figure 13. Cape du Couedic Lighthouse, 1917. Image courtesy of the NAA: A6247, A56/2 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)30

Figure 13. Cape du Couedic Lighthouse, 1917. Image courtesy of the NAA: A6247, A56/2 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)30

An oversight in the lighthouse’s construction also resulted in serious injuries. The lantern

installed at the tower did not arrive with an internal or external catwalk which made cleaning the lantern glazing difficult. The Headkeeper in 1929, H.H. Beare, broke his ribs and suffered internal injuries when he fell approximately 21 metres from the tower while cleaning the glazing. After great difficulty in getting Beare to Kingscote via car, and then onto Adelaide by air, he made a full recovery.31

Due to the rough road to the lighthouse, supplies were delivered via steamer and carried up the haulage way. Mail was delivered by horseback fortnightly.32 By the early 1950’s, shipping along Kangaroo Island had subsided considerably with vessels using Backstairs Passage and Investigator Strait instead.33 By 1957, the lighthouse was automated and the keeper positions were terminated.

3.6 Chronology of major events

The following table details the major events to have occurred at Cape du Couedic Lighthouse.

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 27 June 1909 | Light first exhibited.34 |

| 1910 | Third keeper G. Marment drowned at South Neptune Island while fishing. Body recovered several weeks later.35 |

| 1919 | Flinders Chase National Park established.36 |

| 1929 | Headkeeper Beare falls from the external catwalk and is taken to Adelaide with broken ribs and internal injuries.37 |

| 1940 | First motor vehicle visit to Cape du Couedic.38 |

| 1951 | The manned future of Cape du Couedic Lighthouse called into question after keepers reported seeing only 15 ships pass the lighthouse across three years.39 |

| 1957 | Lighthouse automated and keeper positions terminated. |

| 1959 | Cape du Couedic Lighthouse reserve, excluding the tower and storage shed, were sold to the Flora and Fauna Board of South Australia.40 |

| 1980 | Cape du Couedic Lighthouse listed on the South Australian Heritage Register. |

| 1991 | Keepers cottages restored and made available for tourist accommodation.41 |

| 2004 | Cape du Couedic Lighthouse listed on the Commonwealth Heritage List. |

| 2007 | 60,000 hectares of Flinders Chase National Park and nearby Ravine des Casoars Wilderness Protection Area lost in bushfires. |

| 2020 | Bushfires destroy parts of Flinders Chase National Park, lighthouse tower and cottages left unscathed. |

3.7 Changes and conservation over time

The following section details the changes and conservation efforts to have been carried out at Cape du Couedic Lighthouse since its construction.

The Brewis Report

Commander CRW Brewis, retired naval surveyor, was commissioned in 1911 by the Commonwealth Government to report on the condition of existing lights and to recommend any additional ones. Brewis visited every lighthouse in Australia between June and December 1912, and produced a series of reports published in their final form in March 1913. These reports were the basis for future decision-making for the individual lighthouses and provide a snapshot of the Cape du Couedic lightstation in the early 20th century.42

Cape Couedic Light.

(147 miles from Adelaide; 27 miles from Cape Borda.)

Lat. 35° 46’ S., Long. 136° 42’ E., Chart No. 2389 (a). – Established 1909.

Character.- Main Light.- One white, group flashing two short flashes ea. One-third sec. in quick succession every seven and a-half seconds. Dioptric, 1st Order, 439,000 c.p. Illuminant, vaporized kerosene; 85mm. incandescent mantle.

Circular stone tower, 58 feet, red and white bands. Height of focal plane, 339 feet.

Subsidary Light. – One white, with red sectors. Fixed, Dioptric. Candle-power – white, 10,000; red, 2,500.

Same tower as main light. Height of focal plane, 279 feet.

Visibility.- Main Light. – From seaward, in clear weather, for a distance of 25 nautical miles.

Subsidary Light. – Red, fixed, through an arc of 30 degrees from 359 ½ (N. 5 W., Mag). to 29 ½ (N.

25 E., Mag.), and obscured elsewhere. Visible in clear weather – white, 21 nautical miles; red, about 10 nautical miles.

Optical Apparatus. – Main Light. – Chance Bros., 1909. Dioptric, 1st Order. Focal radius, 36 inches.

Six panels, each 60 degrees horizontal angle. Upper and lower reflecting prisms. Revolved on mercury float. One complete revolution every 22 ½ seconds.

Condition and state of efficacy. – The tower, apparatus, quarters, and equipment are modern, and in good condition.

No Morse signals. These are undesirable, on account of outlying dangers.

Rocket signals are fired to warn vessels running into danger.

Three light-keepers are stationed here.

Communication. – Telephone to Cape Borda Light, 47 miles (no road); thence to Kingscote and main telegraph system.

Mails fortnightly from Kingscote by road, distant 70 miles.

Visited periodically by Government Steamer.

Landing at pier below light station.

Fogs. – Fog was only experienced on two occasions in the year 1911. One lasted twenty minutes, and the other fourteen hours.

Soundings. – Off-lying dangers extend for a distance of 26 miles to the southward of Kangaroo Island. Vessels should, in thick weather, give this part of the coast a wide berth, and maintain a depth of over 60 fathoms – the more the better.

RECOMMENDATION. – Nil.

Alteration to the light

The following table details the changes to the Cape du Couedic light since its exhibition in 1909.

| Date | Alteration |

|---|---|

| 1909 | Chance Bros. 12’9” lantern, 1st Order 6-panel lens with 85mm burner. 3rd Order auxiliary light with two sectors, red and white. |

| 1917 | 3rd Order auxiliary light discontinued. |

| c.1922 | Intensity: 439,000 candelas |

| 1957 | 1st Order 6-panel lens removed. Replaced with 375mm Chance Bros. lens. Light converted to automatic acetylene operation and station de-staffed. |

| July 1974 | Light converted to electric operation. Intensity: 38,000 candelas. |

| 2008 | Optic upgraded to Halogen lamp. Intensity: 17,386 candelas. |

| 2020 | Optic upgraded to LED lighthouse source. |

For information on current light details, see ‘Appendix 4 Cape du Couedic Lighthouse current light details’.

Recent conservation works

The following table details the recent conservation works to have occurred at Cape du Couedic Lighthouse.

| Date | Work |

|---|---|

| 1910 | Catwalk installed at lighthouse. |

| 1957 | Five catwalk floor panels and their brackets removed, and infill floor installed at catwalk level, with timber planks supported on rolled steel joists spanning across the top of the lantern base for acetylene conversion. 1st Order lens and pedestal removed and sent to Eddystone Point Lighthouse (Tasmania). |

| 2015 | Lantern room and upper ring repainted, glazing resealed and broken glazing panes replaced. |

3.8 Summary of current and former uses

From its construction in 1909, Cape du Couedic Lighthouse has been used as a marine AtoN for mariners at sea. Its AtoN capability remains its primary use.

The cottages, once used to house the keepers stationed at Cape du Couedic Lighthouse, were utilised by Flinders University circa. 1980s. At the time this plan was written, the Cape du Couedic cottages are used for tourist accommodation under the management of SA Tourism Kangaroo Island.

3.9 Summary of past and present community associations

Aboriginal associations

The Cape du Couedic landscape maintains high significance due to its long Aboriginal history, and its part within the Ngurunderi Dreaming Story.

The Ramindjeri Heritage Association Inc. draw direct connection to King Condoy, headman of Ramindjeri, and Princess Con. Ramindjeri people observe the island to be a ‘gateway to heaven’, and maintain strong ties to the island and the Cape du Couedic landscape.

Local, national and international associations

Cape du Couedic Lighthouse is considered a significant site to the Kangaroo Island community, as well as to the wider state and national communities due to the site’s contribution to the history of maritime development in the early 20th century. There are also strong familial connections with the site due to its time as a manned station from 1909-1957. The shipwrecks that occurred close to the cape have also cemented the site as one of tragedy and loss.

The surrounding Flinders Chase National Park is notable for its associations with national and international conservation efforts.

3.10 Unresolved questions or historical conflicts

A few dates are contested across various sources. Lighthouses of Australia Inc. determine that construction of the lightstation began in 1906, whereas Garry Searle in their publication “First Order: Australia’s highway of Lighthouses” determines that construction workers first arrived on Kangaroo Island in 1907, and that construction of the lighthouse did not commence until the jetty has been completed.

A full list of the keepers to have been stationed at Cape du Couedic is not available, however a partial list was compiled by Lighthouse of Australia Inc. and the Duthie Family and in available on the Lighthouses of Australia Inc. website.43

3.11 Recommendations for further research

Further investigation on the families stationed at the lightstation would provide greater insight into the social history of the lighthouse during its staffed life-span.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Footnotes

![]() 10 Garry Searle, First Order: Australia’s Highway of Lighthouses, (SA: Seaside Lights, 2013), 34.

10 Garry Searle, First Order: Australia’s Highway of Lighthouses, (SA: Seaside Lights, 2013), 34.

![]() 12 “Cape du Couedic,” Advertiser (Adelaide), December 15, 1905; Sylvia Marchant, Lighthouse history series: Cape du Couedic, South Australia (Department of Transport and Communications, 1989), 1.

12 “Cape du Couedic,” Advertiser (Adelaide), December 15, 1905; Sylvia Marchant, Lighthouse history series: Cape du Couedic, South Australia (Department of Transport and Communications, 1989), 1.

13 “Kangaroo Island,” The Kangaroo Island Courier (Kingscote), July 24, 1936; “Kangaroo Island centenary celebrations,” Northern Angus (Clare, SA), July 31, 1936

![]() 14 Searle, First Order, 371.

14 Searle, First Order, 371.

![]() 15 “Wreck of the Emily Smith,” South Australian Advertiser (Adelaide), May 24, 1887; “Wreck of the Mars,” Narracoorte Hearld, July 3, 1885

15 “Wreck of the Emily Smith,” South Australian Advertiser (Adelaide), May 24, 1887; “Wreck of the Mars,” Narracoorte Hearld, July 3, 1885

16 “Wreck of the Loch Sloy,” Advertiser (Adelaide), May 16, 1899; “The Loch Sloy wreck,” Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), May 10, 1899

![]() 17 “Light on South Neptune Island,” South Australian Register (Adelaide), June 16, 1899

17 “Light on South Neptune Island,” South Australian Register (Adelaide), June 16, 1899

18 Searle, First Order, 371; “A lighthouse needed,” Advertiser, November 12, 1902

19 “Loch Vennachar,” Colac Herald, October 2, 1905

20 Commonwealth Department of Transport, Cape du Couedic: Historical outline (Australian Maritime Safety Authority Archives).

![]() 21 Searle, First Order, 374; “Cape de Couedie Light Station,” Advertiser (Adelaide), November 9, 1908

21 Searle, First Order, 374; “Cape de Couedie Light Station,” Advertiser (Adelaide), November 9, 1908

![]() 23 Searle, First Order, 373; Commonwealth Department of Transport, Cape du Couedic.

23 Searle, First Order, 373; Commonwealth Department of Transport, Cape du Couedic.

24 NAA: A9568, 4/8/1.

25 “Cape de Couedic Lighthouse,” Register (Adelaide), June 29, 1909

26 Searle, First Order, 374.

![]() 27 Searle, First Order, 374; “Advertising,” Advertiser (Adelaide), April 19, 1909

27 Searle, First Order, 374; “Advertising,” Advertiser (Adelaide), April 19, 1909

![]() 28 “Cape de Couedic Lighthouse.”

28 “Cape de Couedic Lighthouse.”

29 Searle, First Order, 375.

30 NAA: A6247, A56/2.

31 Searle, First Order, 376; “Accident at lighthouse,” Argus (Melbourne), May 4, 1929

![]() 32 “Cape Du Couedic Lighthouse,” Lighthouses of Australia Inc., accessed October 2020

32 “Cape Du Couedic Lighthouse,” Lighthouses of Australia Inc., accessed October 2020

33 Searle, First Order, 376; “Cape Due Couedic Lighthouse.”

![]() 34 “Cape de Couedic Lighthouse.”

34 “Cape de Couedic Lighthouse.”

35 Searle, First Order, 375.

![]() 36 “Cape de Couedic Lighthouse.”

36 “Cape de Couedic Lighthouse.”

37 “Injured Lighthouse Keeper,” Argus (Melbourne), May 6, 1929

38 “Cape de Couedic Lighthouse.”

![]() 39 Searle, First Order, 376-377.

39 Searle, First Order, 376-377.

![]() 40 “Cape de Couedic Lighthouse.”

40 “Cape de Couedic Lighthouse.”

41 “Cape de Couedic Lighthouse.”

42 C.R.W. Brewis, Lighting of the South Coast of Australia, (South Australia: Albert J. Mullett Acting Government Printer, 1912), 19-20.

![]() 43 “Cape de Couedic Lighthouse.”

43 “Cape de Couedic Lighthouse.”