3.1 General history of lighthouses in Australia

The first lighthouse to be constructed along Australian soil was Macquarie Lighthouse, located at the entrance to Port Jackson, NSW. First lit in 1818, the cost of the lighthouse was recovered through the introduction of a levy on shipping. This was instigated by Governor Lachlan Macquarie, who ordered and named the light.

The following century oversaw the construction of hundreds of lighthouses around the country. Constructing and maintaining a lighthouse were costly ventures that often required the financial support of multiple colonies. However, they were deemed necessary aids in assisting the safety of mariners at sea. Lighthouses were firstly managed by the colony they lay within, with each colony developing their own style of lighthouse and operational system. Following Federation in 1901, which saw the various colonies unite under one Commonwealth government, lighthouse management was transferred from state hands to the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service.

Lamps and optics: an overview

Lighthouse technology has altered drastically over the centuries. Eighteenth century lighthouses were lit using parabolic mirrors and oil lamps. Documentation of early examples of parabolic mirrors in the United Kingdom, circa 1760, were documented as consisting of wood and lined with pieces of looking glass or plates of tin. As described by Searle, ’When light hits a shiny surface, it is reflected at an angle equal to that at which it hit. With a light source is placed in the focal point of a parabolic reflector, the light rays are reflected parallel to one another, producing a concentrated beam’.8

In 1822, Augustin Fresnel invented the dioptric glass lens. By crafting concentric annular rings with a convex lens, Fresnel had discovered a method of reducing the amount of light absorbed by a lens. The Dioptric System was adopted quickly with Cordouran Lighthouse (France), which was fitted with the first dioptric lens in 1823. The majority of heritage-listed lighthouses in Australia house dioptric lenses made by others such as Chance Brothers (United Kingdom), Henry-LePaute (France), Barbier, Bernard & Turenne (BBT, France) and Svenska Aktiebolaget Gasaccumulator (AGA of Sweden). These lenses were made in a range of standard sizes, called orders—see ‘Appendix 2. Glossary of lighthouse Terms relevant to Swan Island Lighthouse’.

Early Australian lighthouses were originally fuelled by whale oil and burned in Argand lamps, and multiple wicks were required in order to create a large flame that could be observed from sea. By the 1850s, whale oil had been replaced by colza oil, which was in turn replaced by kerosene, a mineral oil.

In 1900, incandescent burners were introduced. This saw the burning of fuel inside an incandescent mantle, which produced a brighter light with less fuel within a smaller volume. Light keepers were required to maintain pressure to the burner by manually pumping a handle as can be seen in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Incandescent oil vapour lamp by Chance Brothers (Source: AMSA)

Figure 8. Incandescent oil vapour lamp by Chance Brothers (Source: AMSA)

In 1912, Swedish engineer Gustaf Dalén, was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for a series of inventions relating to acetylene-powered navigation lights. Dalén’s system included the sun valve, the mixer, the flasher, and the cylinder containing compressed acetylene. Due to their efficiency and reliability, Dalén’s inventions led to the gradual demanning of lighthouses. Acetylene was quickly adopted by the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service from 1915 onwards.

Large dioptric lenses, such as that shown in Figure 9, gradually decreased in popularity due to cost and the move towards unmanned automatic lighthouses. By the early 1900s, Australia had stopped ordering these lenses with the last installed at Eclipse Island in Western Australia in 1927. Smaller Fresnel lenses continued to be produced and installed until the 1970s when plastic lanterns, still utilising Fresnel’s technology, were favoured instead. Acetylene remained in use until it was finally phased out in the 1990s.

Figure 9. Dioptric lens on display at Narooma (Source: AMSA)

Figure 9. Dioptric lens on display at Narooma (Source: AMSA)

In the current day, Australian lighthouses are lit and extinguished automatically using mains power, diesel generators, and solar-voltaic systems.

Figure 10. Dalén's system - sunvalve, mixer, flasher and cylinder (Source: AMSA)

Figure 10. Dalén's system - sunvalve, mixer, flasher and cylinder (Source: AMSA)

3.2 The Commonwealth Lighthouse Service

When the Australian colonies federated in 1901, they decided that the new Commonwealth government would be responsible for coastal lighthouses—that is, major lights used by vessels travelling from port to port—but not the minor lights used for navigation within harbours and rivers. There was a delay before this new arrangement came into effect. Existing lights continued to be operated by the states.

Since 1915, various Commonwealth departments have managed lighthouses. AMSA, established under the Australian Maritime Safety Authority Act 1990 (Cth), is now responsible for operating Commonwealth lighthouses and other aids to navigation, along with its other functions.

3.3 Tasmanian Lighthouse Service Administration

| Time Period | Administration |

| 1915-1927: | Lighthouse District No. 3 (Victoria, New South Wales, Tasmania), Hobart Headquarters. |

| 1927-1963: | Deputy Director of Lighthouses and Navigation, Tasmania. |

| 1963-1972: | Department of Shipping and Transport, Regional Controller, Tasmania. |

| 1972-1982: | Department of Transport , Regional Controller, Tasmania. |

| 1982-1983: | Department of Transport and Construction. Victoria-Tasmania Region, Transport Division (Tasmania). |

| 1983-1985: | Department of Transport Victoria-Tasmania Region, Hobart Office. |

| 1985-1987: | Department of Transport , Tasmanian Region. |

| 1987-1990: | Department of Transport and Communications, Tasmanian Region. |

| 1991- | Australian Maritime Safety Authority. |

3.4 Swan Island: a history

Aboriginal history

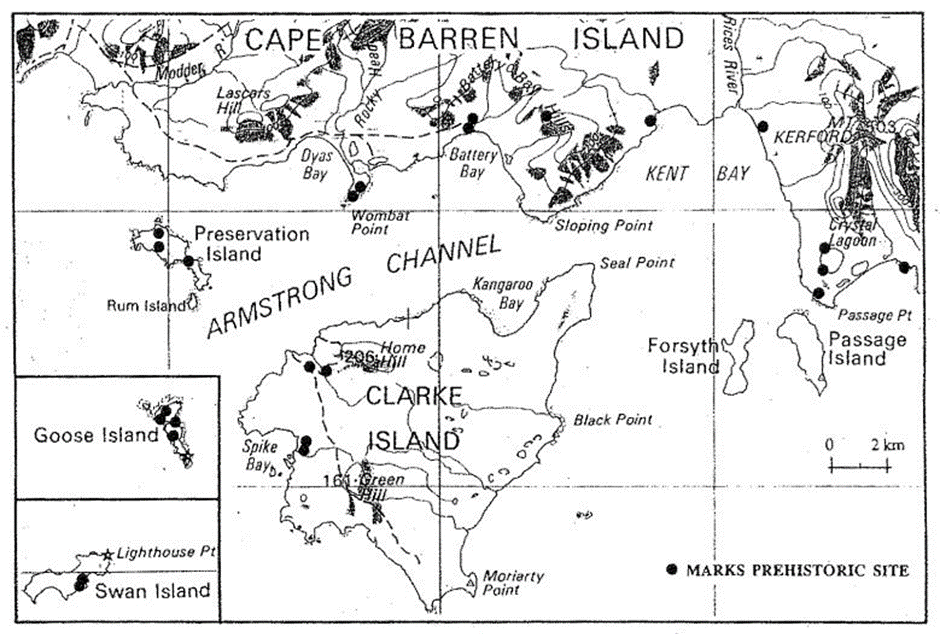

Surveys of the Outer Furneaux Islands were carried out in 1989-1990 and a total of 64 prehistoric Aboriginal sites were recorded, all containing stone artefacts. Sites recorded on Swan Island were identified as being open sites consisting of stone artefacts of quartz, quartzite and exotic. Seven unretouched flake and flaked pieces, and three retouched implements were identified within Swan Island’s artefact scatters and are estimated to date from the late Pleistocene landbridge phase.9 These investigations demonstrated that the eastern Bassian region was occupied during the prehistoric period.

Aboriginal Heritage Tasmania (Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, TAS) detailed that two significant sites recorded are registered Aboriginal heritage sites. These sites are located outside of the AMSA lease.

Figure 11. Sites recorded during 1989-1990 investigation (Image courtesy of Dr Robin Sim) 10

Figure 11. Sites recorded during 1989-1990 investigation (Image courtesy of Dr Robin Sim) 10

Following European exploration and inhabitation of Bass Strait, the Pairrebeenne People were forcibly removed from their own Country to Swan Island for a period of time in 1830. 11

The full extent of past and present Aboriginal cultural associations with Swan Island requires further research. New information will be included in later versions of this plan.

Early European history

In 1798, the passage of water separating Tasmania from the mainland was charted by British explorer George Bass, and British navigator and cartographer Matthew Flinders. Named ‘Bass Strait’, this passage was traversed by countless ships that had previously been forced to journey around the south coast of Tasmania. 12

The Waterhouse Group Islands were named after Captain Henry Waterhouse, a British Officer of the Royal Navy who was heavily involved in establishing early colonial settlements throughout the south-east of Australia. Swan Island was among those listed within the Waterhouse Group Islands. 13

Knowledge on the history of Swan Island following Bass and Flinders’ expedition and prior to the construction of the lighthouse is limited, however it is understood seal hunting was prevalent in the region from at least 1805. 14

3.5 Planning a lighthouse

Why Swan Island?

In 1841, Sir John Franklin, the Lieutenant Governor of Van Diemen’s Land, recommended to Sir George Gipps, the Governor of New South Wales, that two lights be constructed in a section of Bass Strait known as Banks Strait. Following the settlement of Port Phillip in 1835, shipping between Melbourne, Hobart and Launceston had increased substantially. As a result, requests for safer passage through the Strait had grown in abundance. Swan Island was recommended as a lighthouse site as the Island’s position harnessed the potential to provide a landfall mark for ships bound for Melbourne and northern Tasmanian ports from the South Tasman Sea. 15

Construction

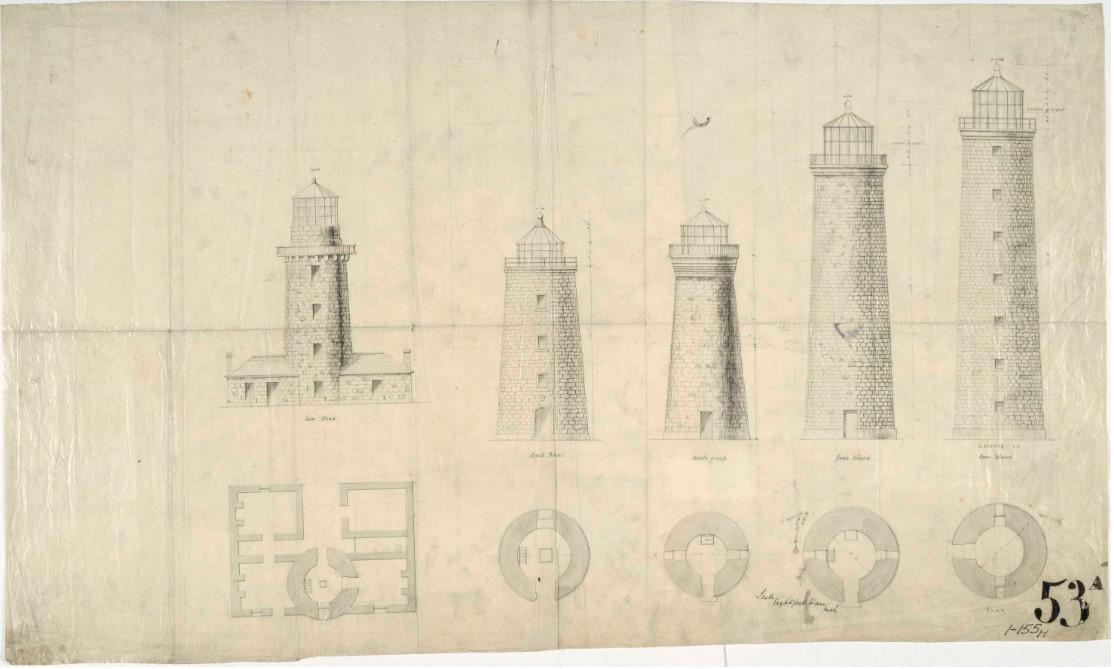

Construction on the Swan Island lighthouse was led by ex-convict Charles Watson and his team of convicts. Prior to construction, Watson’s team had been working on the Goose Island Lighthouse to the north of Banks Strait, however the delayed delivery of a lantern then forced the builders to start on the Swan Island Lighthouse with Governor Franklin laying the first stone on 22 November 1843. At a cost of 2,300 pounds, construction saw the quarrying of granite from the Island itself. 16

Figure 12. Drawings and floor plans of five Tasmanian lighthouses built in 1840s. From left to right: Low Head, South Bruny, Deal Island, Swan Island, and Goose Island (1848). Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A9568, 5/10/1 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Figure 12. Drawings and floor plans of five Tasmanian lighthouses built in 1840s. From left to right: Low Head, South Bruny, Deal Island, Swan Island, and Goose Island (1848). Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A9568, 5/10/1 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

style="box-sizing:inherit;font-size:12px;line-height:0;position:relative;top:-0.5em;vertical-align:baseline;">17</sup></a>">

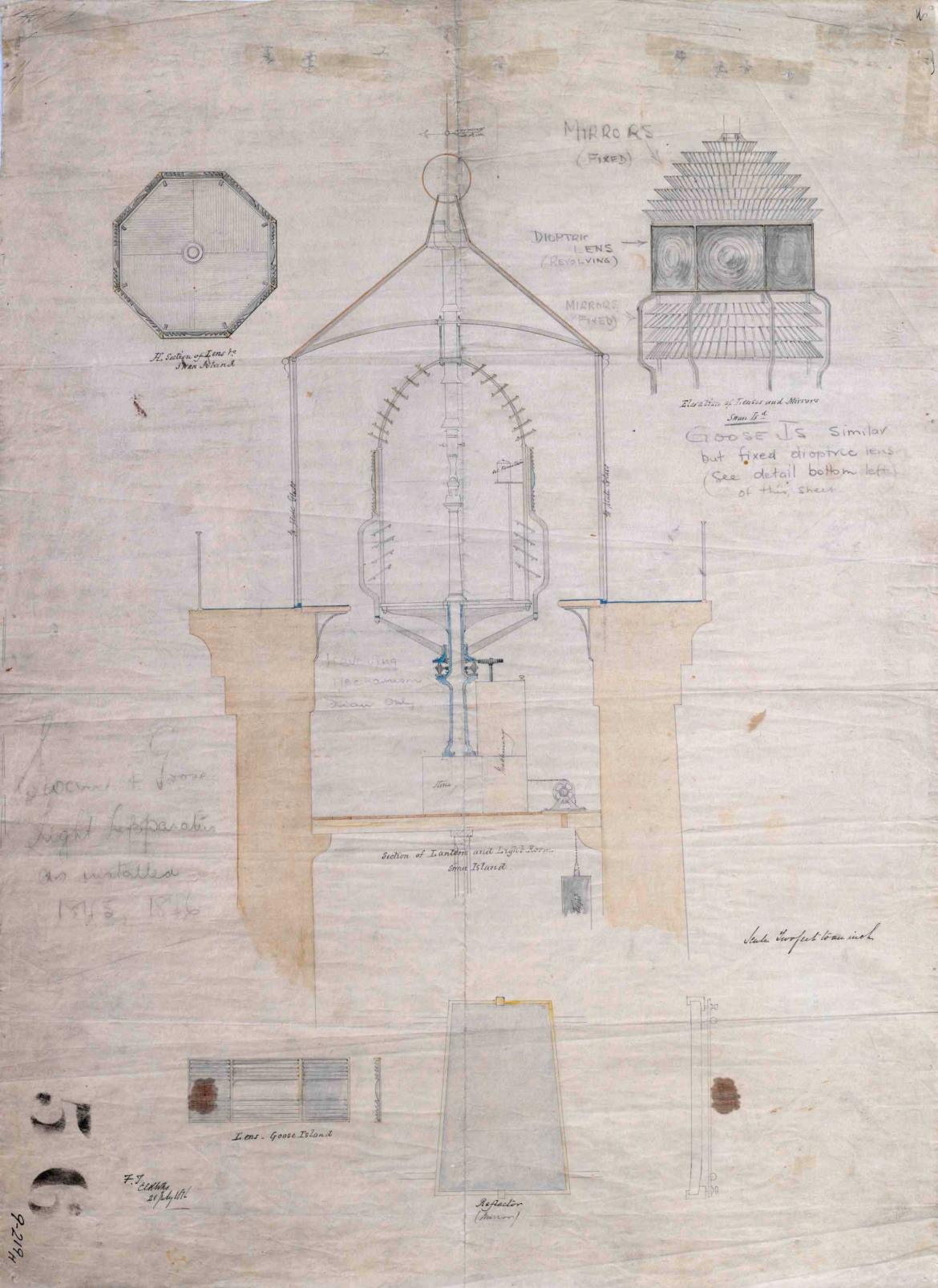

Figure 13. Swan Island Lighthouse - Light Apparatus as Installed 1845/1846. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A9568, 5/9/3 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia) 18

Figure 13. Swan Island Lighthouse - Light Apparatus as Installed 1845/1846. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A9568, 5/9/3 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia) 18

Equipment when built

The lighthouse was completed in late 1845 and the light was first exhibited on 1 November of the same year making Swan Island the first finished lighthouse within Bass Strait.

Upon completion, Swan Island Lighthouse stood as a 27m, white-painted, granite rubble tower fitted with a catadioptric lens system. The original light was that of a 12’ 11/2” diameter lantern by Wilkins and Co. with fixed silvered upper and lower mirrors.

The Weekly Register of Politics, Facts and General Literature documented the tower in its finished state:

The revolving light comprises one concerntrated lamp, with three hundred and fifty-two stationary mirrors, of which two hundred and twenty are placed in the form of a dome, above the concentrated lamp, and one hundred mirrors are fixed in a diagonal line from the concerntrated lamp, and twenty-eight below the concentrated lamp, facing each other. The revolving apparatus consists of an iron column, revolving rollers which work round, with arms and uprights, &c., which supports eight refractors or glass lenses of two feet six inches square each – made of a number of circular pieces of polished glass – the refractors work in the open space between the upper and lower mirrors. The clock-work is a splendid piece of mechanism, which will be lighted up on the 1st of November next. The light-house is under the superintendence of Mr. Charles Watson.19

The use of a single lamp meant that only one gallon of oil a night was required to power the lighthouse.

Entry into the lantern room originally required keepers to scale eight ladders fixed to the internal walls of the tower before a freestanding spiral staircase was installed in 1893. 20

3.6 Lightkeeping on Swan Island

The lighthouse was originally presided over by a superintendant and a small number of convict assistants. The first superintendant, W Johnston, was provided with a cottage onsite whilst his assistants were forced to reside in crude shelters. These shelters were considered so inadequate that the assistants would set up camp in the base of the lighthouse tower itself. Eventually in 1850, another spacious four-bedroom cottage was constructed onsite for the superintendant, and his assistants moved into the original cottage. 21

Figure 14. Swan Island Lighthouse and cottage, 1917. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A6247, B4/3 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Figure 14. Swan Island Lighthouse and cottage, 1917. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A6247, B4/3 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Life on the island was relatively isolated throughout the mid to late 19th century and not without incident. The venomous tiger snake prevalent on Swan Island led to regular hunts around the island with light keepers often boasting of their kill count. In November 1933, the lightkeeper’s 15 year old son, Roy Patterson, was fatally shot in the chest by his friend Lawrence Williams while out hunting tiger snakes. Williams had accidentally fired his gun after tripping and falling over a tussock. Patterson died at the scene and his body was taken to the mainland by passing steamer Kowhal. 22

Shipwrecks were also common around the island and the lighthouse was often the first point of call for those escaping distressed vessels. In 1952, four men became stranded on Swan Island following the wrecking of their fishing boat Two Brothers. The lightkeepers stationed at the tower alerted the mainland and cared for the men until a rescue boat could be deployed from Bridport. 23

3.7 Major events

The following table outlines the major events to have occurred at Swan Island Lighthouse from its construction to current day.

| Date | Event |

| 1 Nov 1845 | Light first exhibited from Swan Island Lighthouse. |

| 1850 | New cottage constructed for Superintendant, named ‘Eliza’s Cottage’ following the death of the lightkeeper’s wife Eliza. |

| 1886 | Lighthouse connected with telegraph system.24 |

| 1893 | Temporary lighthouse erected on Swan Island as original lighthouse is renovated.25 |

| 28 Sept 1908 | Lightkeepers report a ship wrecked off Little Swan Island – four survivors.26 |

| 1927 | Fibro assistant’s cottage built. Original 1845 cottage abandoned. |

| 1933 | Son of lightkeeper accidentally shot dead by friend while out hunting tiger snakes.27 |

| 1936 | Radio communication established on island. |

| 1952 | Fishing boat wrecked in Bass Strait – four survivors taken in by Swan Island lightkeepers.28 |

| 27 Mar 1984 | Swan Island Lighthouse included on the Register of the National Estate. |

| 1986 | Lighthouse demanned. |

| 1987 | Swan Island (excluding lightstation) placed for sale.29 |

| 1990 | Swan Island (excluding lightstation) sold and is tranformed into holiday accomodation.30 |

| 22 Jun 2004 | Swan Island Lighthouse included on the Commonwealth Heritage List. |

3.8 Changes and conservation over time

Owing to technological improvements made to navigational aids over the course of the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries, the Swan Island lighthouse underwent a number of alterations.

The Brewis Report

Commander CRW Brewis, retired naval surveyor, was commissioned in 1911 by the Commonwealth Government to report on the condition of existing lights and to recommend further additions. Brewis visited every lighthouse in Australia between June and December 1912 and produced a series of reports published in their final form in March 1913. These reports were the basis for future decisions made in relation to the individual lighthouses.

Recommendations made by Brewis included altering the character of the light, increasing the power of the light to 100,00 c.p., installing a Morse signal lamp and erecting a new oil store and workshop.31

(20 miles from Eddystone Point.)

Lat. 40º 44’ S., Long. 148º 8’ E., Chart No. 1706. – Established in the year 1845; last altered 1894.

Character.- One white, fixed and flashing every minute. Dioptric, 1st Order, 20,000 c.p. Illuminant, kerosene.

Stone tower, 74 feet. Height of focal plane, 100 feet above high water. Visible, in clear weather, 16 nautical miles.

Condition and State of Efficiency.- The light-house tower and apparatus are in good condition.

Clockwork mechanism has been renewed recently. By regulating the governor of this mechanism, the

speed of the flashes can be considerably increased.

The buildings are old, but servicable. The sand blows have depreciated the land to a great extent.

A new oil store and workshop are required.

Three light-keepers are stationed here.

Communication.- Quarterly by steamer carrying stores by contract.

An acetylene Morse Lamp is required, to facilitate communication with passing vessels – necessary

in case of emergency.

RECOMMENDED.-

(a) The period of the light be increased to fixed and flashing every 30 seconds. No cost will

be incurred in carrying this out, as the Head Light-keepers can effect the adjustment.

(b) The power of the light be increased from 20,000 to 100,000 c.p., and economy effected

in the consumption of oil by installing an 85 mm. incandescent mantle; illuminant,

vaporized kerosene.

(c) Acetylene Morse signal lamp be provided.

(d) New oil store and workshop be erected.

Alteration to the light

Changes to the light at Swan Island Lighthouse have occurred due to advances in technology. The table below lists the alterations made.

| Date | Alterations |

| 1923 | Wickburner replaced with incandescent kerosene burner. |

| 1938 | Converted to diesel-electric operation. |

| 1985 | Converted to PRB 24/4 beacon powered by wind generator. Lantern roof sheets replaced with GRP replicas. |

| 1990 | Converted to solar power. |

| 2006 | VRB 25 beacon installed. |

Conservation works

The following table lists the rectification works undertaken to maintain the lighthouse.

| Date | Works Completed |

| 1893 | Timber ladders and immediate floors replaced with freestanding cast iron spiral stair and central column/weight tube.32 |

| 2012 | Oil store building refurbishment. Roof cladding, gutters and downpipes replaced with stainless steel products. Interior and exterior wall cladding replaced with fibre cement sheet. |

| 2015 | Minor asbestos sheeting removal. Minor repaint. |

3.9 Summary of current and former uses

From its construction in 1845, Swan Island Lighthouse has been used as a marine AtoN for mariners at sea. Its AtoN capabilities remains its primary use.

Currently, the lighthouse tower is accompanied by:

- Oil store – currently unused

- Building remnant (original use unknown) – currently used as a helipad

3.10 Summary of past and present community associations

Aboriginal associations

Further consultation with traditional stakeholders is required for a greater understanding of the past and present associations held across the region.

Local, national and international associations

As one of the oldest lighthouse towers to have remained active, Swan Island Lighthouse maintains significant national ties to both historic and current day navigational safety. Convict and lightkeeping familes’ presence on the island has generated genealogical interest in the region both locally, nationally and internationally.

3.11 Unresolved questions or historical conflicts

Knowledge on the history of the growth of Swan Island is limited. Details of the original lightstation indicate that a cottage and ‘crude shelters’ were built beside the lighthouse, however little mention is made of other buildings constructed onsite in 1845.33 Some sources indicate a jetty and boatshed were built on the island at some stage and later burnt down in 1982. 34

3.12 Recommendations for further research

Now a privately owned island, Swan Island’s population was originally restricted to the lightkeepers. Tracking the growth of the island and the construction of its airstrip and additional buildings would be valuable in gaining an in-depth understanding of the island’s history.

Research on past lighthouse keepers of Swan Island, particularly the role of convict assistants, may be beneficial in determining the full extent of the social value placed on the site.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Footnotes

![]() 8 Garry Searle, First Order: Australia’s Highway of Lighthouses, (SA: Seaside Lights, 2013), 34.

8 Garry Searle, First Order: Australia’s Highway of Lighthouses, (SA: Seaside Lights, 2013), 34.

![]() 9 Sim, R. The Archaeology of Isolation? Prehistoric Occupation in the Furneaux Group of Islands, Bass Strait, Tasmania, PhD, ANU (1998), pg. 45-58.

9 Sim, R. The Archaeology of Isolation? Prehistoric Occupation in the Furneaux Group of Islands, Bass Strait, Tasmania, PhD, ANU (1998), pg. 45-58.

![]() 10 Sim, R., The Archaeology of Isolation?, PhD, ANU (1998), pg. 349.

10 Sim, R., The Archaeology of Isolation?, PhD, ANU (1998), pg. 349.

![]() 11 Furneaux Historical Research Association Inc. Tasmanian Aboriginal History in the Furneaux Region, Flinders Council, TAS. https://www.flinders.tas.gov.au/aboriginal-history; Tim Morgan, ‘Aboriginal warrior and diplomat Mannalargenna still showing the way forward, elder says’, ABC News, Dec 4, 2017, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-12-04/aboriginal-warrior-mannalargenna…;

11 Furneaux Historical Research Association Inc. Tasmanian Aboriginal History in the Furneaux Region, Flinders Council, TAS. https://www.flinders.tas.gov.au/aboriginal-history; Tim Morgan, ‘Aboriginal warrior and diplomat Mannalargenna still showing the way forward, elder says’, ABC News, Dec 4, 2017, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-12-04/aboriginal-warrior-mannalargenna…;

![]() 12 Iain Davidson and David Roberts, ’14 000BP – On being along: the isolation of Tasmania,’ Turning Points in Australian History, Martin Crotty and David Roberts (eds), Sydney: UNSW Press, 2009, pg. 20.

12 Iain Davidson and David Roberts, ’14 000BP – On being along: the isolation of Tasmania,’ Turning Points in Australian History, Martin Crotty and David Roberts (eds), Sydney: UNSW Press, 2009, pg. 20.

![]() 13 Vivienne Parsons, ‘Waterhouse, Henry (1770-1812),’ Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol. 2, 1967, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/waterhouse-henry-2775

13 Vivienne Parsons, ‘Waterhouse, Henry (1770-1812),’ Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol. 2, 1967, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/waterhouse-henry-2775

14 Kostoglou, P., Sealing in Tasmania: a historical research project, Hobart, Tas: Dept.of Environment and Land Management, (1996), pg. 78.

![]() 15 Searle, G., First Order (2013), pg. 38

15 Searle, G., First Order (2013), pg. 38

16 Searle, G., First Order (2013), pg. 38

![]() 17 NAA: A9568, 5/10/1

17 NAA: A9568, 5/10/1

18 NAA: A9568, 5/9/3

19 ‘South Australia,’ The Weekly Register of Politics, Facts and General Literature, Oct 11, 1845

![]() 20 Searle, G., First Order (2013), pg. 39

20 Searle, G., First Order (2013), pg. 39

![]() 21 Searle, G., First Order (2013), pg. 41

21 Searle, G., First Order (2013), pg. 41

![]() 23 ‘Wrecked men still at island lighthouse,’ The Mercury, Jan 2, 1952

23 ‘Wrecked men still at island lighthouse,’ The Mercury, Jan 2, 1952

24 ‘Swan Island Lighthouse,’ The Telegraph, Jul 2, 1886

![]() 25 ‘Swan Island Lighthouse,’ The Mercury, Jan 13, 1893

25 ‘Swan Island Lighthouse,’ The Mercury, Jan 13, 1893

![]() 26 ‘Swan Island Lighthouse,’ Daily Telegraph, Oct 1, 1908; ‘The Loch Finlas Wreck: survivors’ thrilling story,’ Daily Telegraph, Sept 29, 1908

26 ‘Swan Island Lighthouse,’ Daily Telegraph, Oct 1, 1908; ‘The Loch Finlas Wreck: survivors’ thrilling story,’ Daily Telegraph, Sept 29, 1908

![]() 27 ‘Boy shot dead: Swan Island accident,’ Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, Nov 14, 1933

27 ‘Boy shot dead: Swan Island accident,’ Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, Nov 14, 1933

![]() 28 ‘Wrecked men still at island lighthouse,’ The Mercury, Jan 2, 1952

28 ‘Wrecked men still at island lighthouse,’ The Mercury, Jan 2, 1952

29 Searle, G., First Order (2013), pg. 45

30 Searle, G., First Order (2013), pg. 45

![]() 31 Brewis, C R W., Preliminary report on the lighting of the coast of Tasmania and the islands in Bass Strait: Recommendations as to existing lights and additional lights, Department of Trade and Customs, (1912), pg. 10.

31 Brewis, C R W., Preliminary report on the lighting of the coast of Tasmania and the islands in Bass Strait: Recommendations as to existing lights and additional lights, Department of Trade and Customs, (1912), pg. 10.

32 Searle, G., First Order (2013), pg. 39

33 Lighthouses of Australia Inc., ‘Swan Island Lighthouse,’ (n.d.)

![]() 34 Lighthouses of Australia Inc., ‘Swan Island Lighthouse,’ (n.d.)

34 Lighthouses of Australia Inc., ‘Swan Island Lighthouse,’ (n.d.)